There are many different types of washplants on the market today. The one thing that they all have in common is that everyone says theirs is the best! We’re not setting out to prove which plant is the best, this article will explore different types of plants and their strengths and weaknesses. Different plants are suitable for different conditions. There is no one size fits all solution.

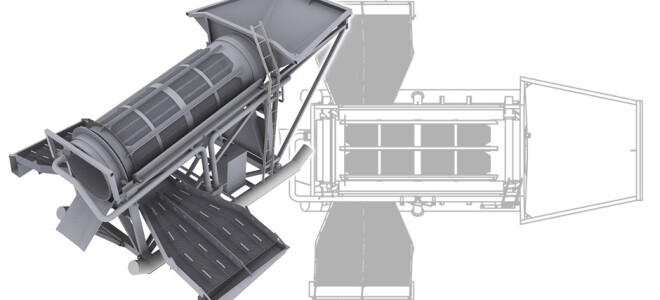

There are 4 main components to a wash plant: Scrubber, Concentrator, Feed System, and Carrier. While no two wash plants are identical they all involve a combination of these 4 components.

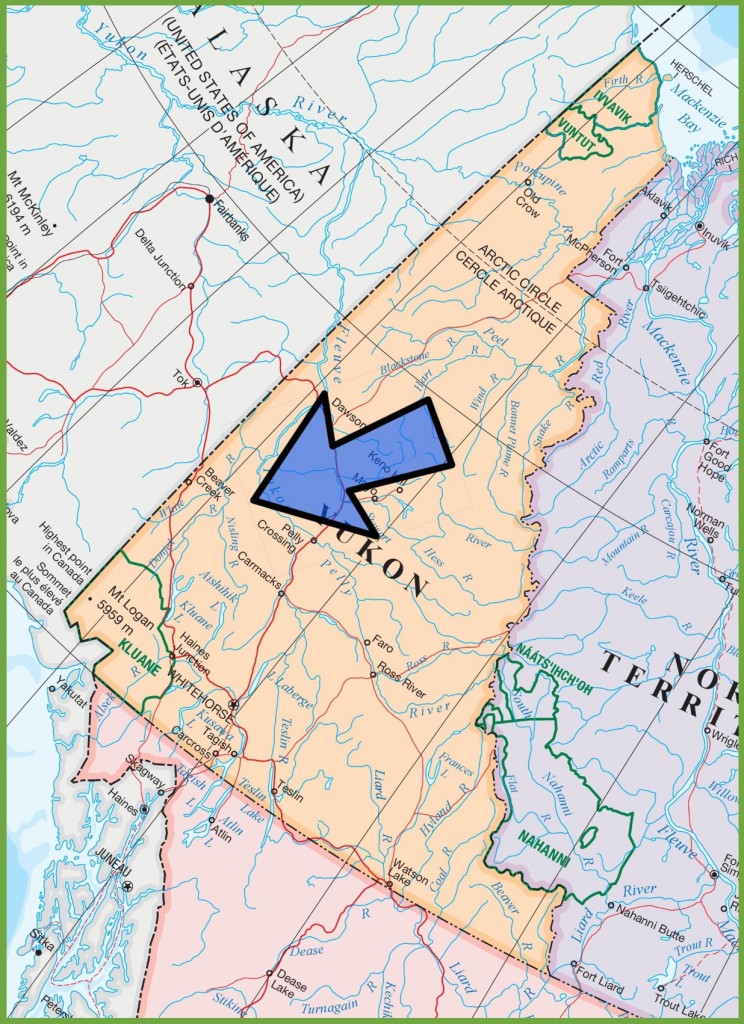

Take a typical trommel plant that you would find in BC or the Yukon for example. You’ll have a hopper that is fed by an excavator, a trommel that feeds a sluice box and it’s mounted on skids.

Scrubbers

The scrubber is the component of a wash plant that separates raw material and prepares it for concentration. The scrubber will remove large rocks and break down chunks of clay and packed sand. Most scrubber systems use water jets to wash the gravel to remove the fine gold that is attached to the cobbles.

The sand and clay that adheres to pebbles and rocks has been shown to have much higher gold content than the gravel as a whole. For that reason, it is important to wash your material well so that gold can be captured in the concentrator.

The scrubber has three main functions:

- Separate large cobbles and boulders from the feed gravel

- Wash the cobbles and gravel

- Break up clods of agglomerated material

The five categories of scrubbers in use today are the Screen Deck, Trommel, Reverse Trommel, Derocker, and Grizzly.

Trommels

Trommels use a rotating drum to agitate the material. Raw gravel is fed at one end and passes over openings in the drum. Rocks that are larger than the openings are disposed of as tailings. The drum is set at a slight angle to allow the tailing rocks to work their way off the end. Trommels do an excellent job of breaking up clay, mud, and compacted gravels.

A trommel is driven by an electric or gasoline-powered motor. The motor spins the drum by either using a long chain with cogs welded around the drum or by wheels that the drum sits on. Most trommels will have a spray bar running inside the drum that sprays high-pressure water on the gravel to aid in removing gold particles from the rocks. The trommel has a lot of moving parts which is one drawback. The more complex a system is, there more potential for failure.

In North America trommels are most often paired with a sluice box that is positioned at a right angle to the drum. A section of openings are positioned above the sluice box with metal screens to allow specific sizes of particles through. Each mine has different requirements for particle sizes depending on the size of gold that exists there. Miner’s typically have openings of 1/2″ or 3/4″, the size of the opening depends on the distribution of gold sizes in the pay gravels.

Trommels can be paired with any type of concentrator, it doesn’t have to be a sluice. Trommels can be any size. They vary from the Gold Cube trommel which is 5” in diameter and 16” long to plants that can run hundreds of yards per hour with diameters of 8 feet or more. Trommels are relatively easy to set up and can handle a wide range of materials. The big advantage that they have over other scrubbers is the ability to break up cemented or compacted material.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Can handle different kinds of material | Mechanically complex, requires maintenance |

| Can handle high volume | Large footprint |

| Relatively easy setup | Burn a lot of fuel |

| Breaks up clay and compacted gravel | Large trommels are difficult to move |

Screen Decks

Screen decks use a series of vibrating screens and water jets to wash gravel and separate large rocks. Each deck is mounted on an angle and suspended by springs and caused to vibrate by mechanical means. There can be multiple decks used or just one.

Like a trommel, screen decks are fed at one end and allow oversize material to fall off the other end. There are perforations in between which allow material to fall through to the lower section. The vibration is caused by the rotation of an unbalanced weight called an “exciter”. That is actually the same thing that causes your cell phone or an Xbox controller to vibrate just on a much larger scale. The exciter is driven by a gas or electric motor. Some smaller models such as the Goldfield Prospector drive the exciter by a pelton wheel using water power alone and no motor.

A series of high-pressure water jets are used to wash material as it vibrates. Screen decks allow for well-positioned water jets to be put in place for thorough washing of gravels and rocks. There are a variety of screen options varying from woven wire, to punch plates and rubber or plastic perforated material. Screen sizes vary depending on the gold distribution and material being processed, customization of screen sizes is easy to achieve.

Screen decks can accomplish very high production in the right materials. Some of the largest wash plants in the world are using screen decks for that reason. Unlike a trommel, screen decks do not handle clay or compacted material very well. It tends to bounce off the screens and roll off the end. Despite the violent nature of vibrating beds the screen deck is a relatively simple machine and does not require a lot of maintenance. The only part that is mechanically driven is the exciter and there aren’t a lot of moving parts compared to a trommel or a derocker.

Screen decks tend to be quite high off the ground (at least large scale wash plants). They generally require enough of an elevation difference at the site to be able to feed the hopper and allow room for a concentrator below. Some miners use a conveyor system to get around this problem but mobility is not the screen deck’s strong suit. They work best in a stationary position where they will be used for a long period of time.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| High volume | Struggles with clay and compacted material |

| Mechanically simple | Large footprint |

| Fuel-efficient | Difficult to move |

| Separation of multiple sizes | Slow to set up |

Reverse Trommels

There are a few variations of reverse trommels that work a little differently than a basic trommel. A reverse trommel allows heavy material (ie. gold) to exit one end while the large rocks and waste material exit the other. Reverse trommels often have a double tube design with an inner trommel that screens the material while the outer trommel has a screw-like helix that separates the gold.

The trommel is set at the appropriate angle to allow gold to exit one end while water flows over the outer tube. The helix acts in a similar way to a gold wheel, the material of higher density is allowed to work it’s way up the spiral and exit on one end, the less dense material falls out the other.

There are some models with only one opening that kind of resembles a cement mixer. The APT RG-30 for example. They work in a similar way with a helix and a carefully positioned angle and rate of water flow.

Reverse trommels are popular in the mid-sized range from 1 to 10 yard per hour units. There are quite a few on the market. One popular unit is the Mountain Goat Trommel which is a hobby-level clean-up machine. There are large-scale commercial versions and everything in between.

Reverse trommels are interesting machines and work well once they’re set up but they are much more complicated machines than a basic trommel and are finicky to set up. They also require a lot of maintenance. That’s one reason they are mostly on the small-scale side of the industry.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Can produce very clean concentrate | Require a lot of maintenance |

| Break up clay very well | Slow setup |

| Separation of multiple sizes | Complicated machinery, lots of moving parts |

| Some designs are very compact | Not very fuel-efficient |

Derockers

Derockers are a neat machine. They use a flexible deck made of long flat slabs with spaces between them. Under the deck is a carriage frame with truck tires that moves back and forth. There is a high-pressure spray system overhead that washes all the material. As the undercarriage moves back and forth it rolls the rocks around on the deck. The water and rolling action work together to wash off the rocks and allow smaller-sized pebbles and material to fall through the openings in the deck slats (usually 2” minus).

Derockers work really well in areas where there are a lot of large rocks and slabs. They are called “de-rockers” after all. They can handle some clay, due to the rolling action they can break it up somewhat. The derocker was invented in the Yukon to deal with gravel deposits that are full of boulders. These machines can easily handle boulders or slabs up to 4 feet in diameter, which would break other types of separation equipment.

Compared to some of the other scrubbers such as screen decks and trommels, the derocker is a complex machine with a lot of moving parts. You have a carriage that takes a beating, the deck has a lot of links to maintain but the derocker frame itself is stationary.

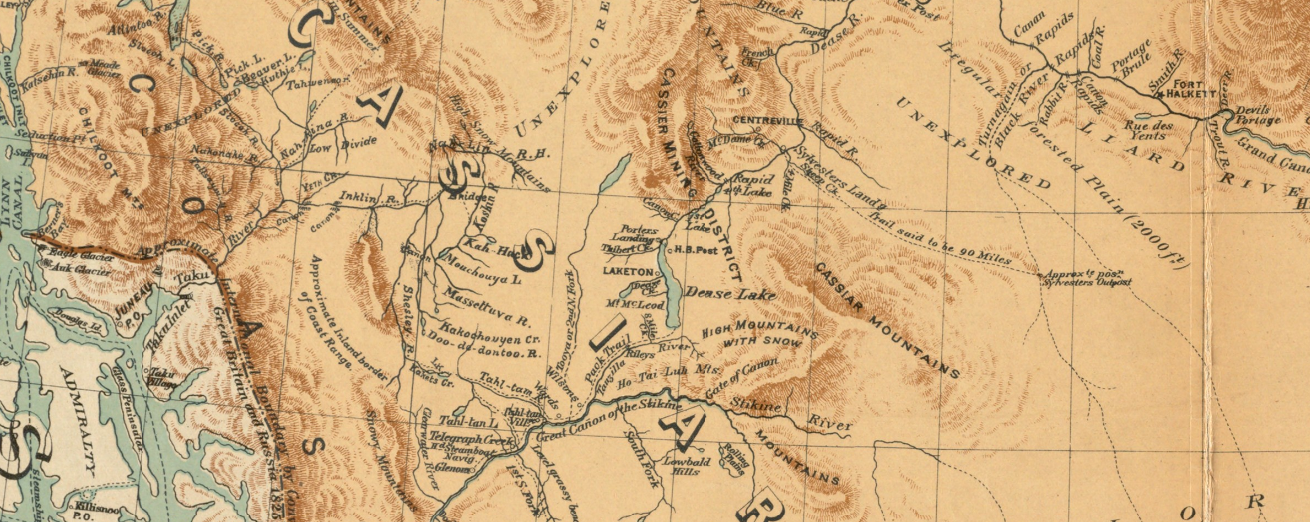

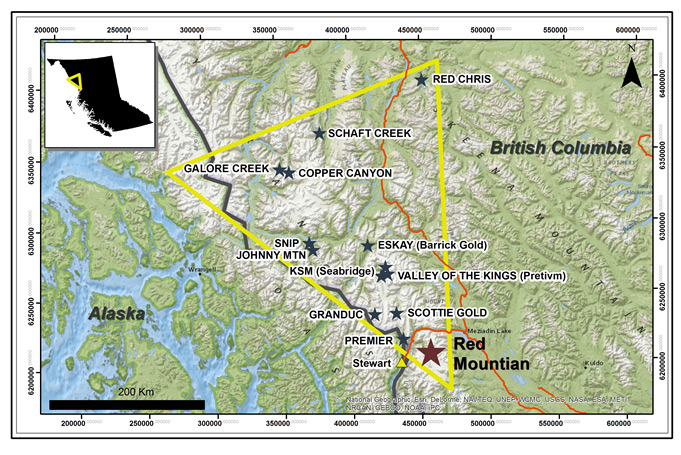

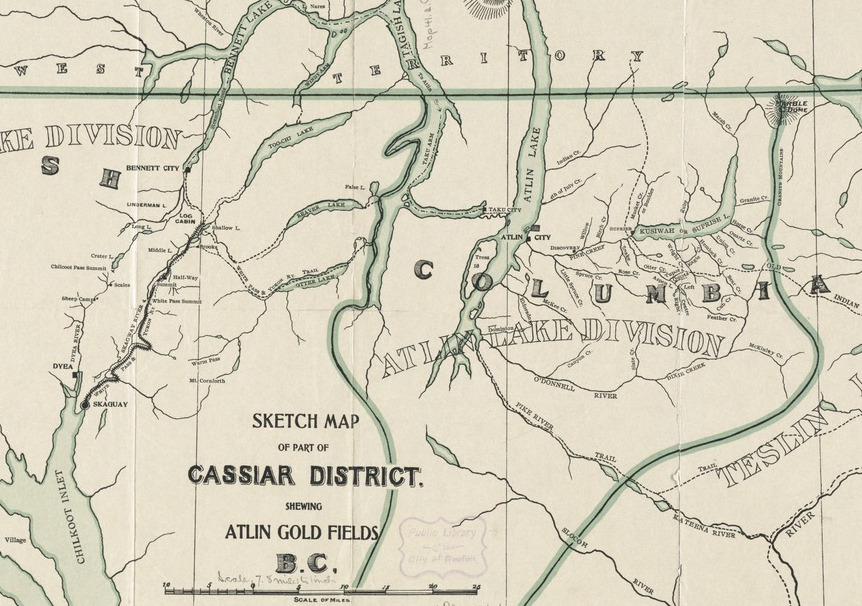

There was a variation of the derocker in the 1980s called the Super Sluice, made by a company called Gold Machines Inc, that used metal fingers instead of the flexible deck. The Super Sluice was very popular for about 10 years in the Cariboo, Klondike and Atlin but over time the complexity of the machine led to frequent breakdowns and they are very few still in use today.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Handles large boulders and slabs | Require a lot of maintenance |

| Can break up clay and compacted material | Complicated machinery, lots of moving parts |

| Very high production with the right material | Require a lot of water and power to run |

| Quick setup, easy to feed | No adjustment for screening options |

Grizzly

Some wash plants don’t have a mechanical separation system at all, some use a simple grizzly. A grizzly consists of vertical bars with spacing to allow the size of material you want to pass through. The grizzly is set on an angle such that the larger rocks will roll off and the stuff that fits through the bars will pass through.

Highbankers and small test plants use a grizzly. Production is slow and they often require manual intervention to clear the large material that collects below. Grizzlys are often incorporated into other separation equipment such as screen decks and trommels.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| No moving parts, no breakdowns | Slow production |

| No motors needed | No ability to clear tailings |

| Easy to move, no setup required | Screened material is still coarse |

| Easy to change for different size of gravel |

Concentrators

The concentrator is the heart of a washplant. It’s the part of the wash plant that catches the gold and other dense material.

Placer concentrators all use gravity and inertia to separate material based on density. Gold is very dense, it has a density of 19,300 kg/m³. That means that one cubic meter of gold would weigh 19,300 kilograms (19.3 metric tons). In contrast, the typical gangue minerals such as quartz sand have a density of 2,700 kg/m³ and the black sands have a density of about 5,200 kg/m³.

All concentrating methods depend on this principle, except for the use of mercury but that’s not used in large-scale placer mining.

The Sluice Box

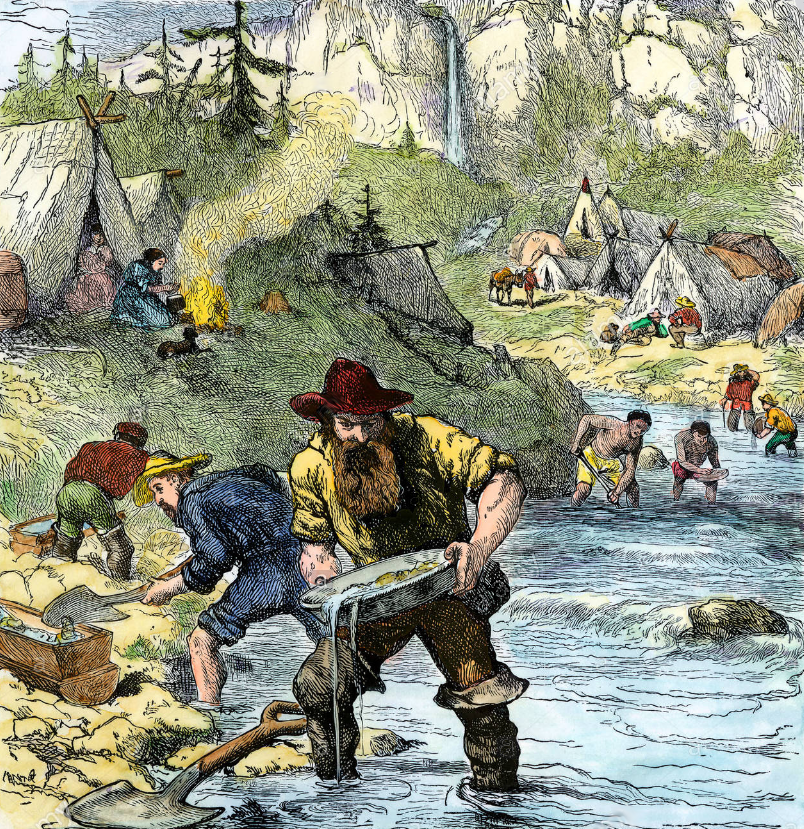

In North America, the sluice is the most common concentrator on commercial placer gold wash plants. The sluice box was developed during the California gold rush around in 1849. The first sluices were called Long Toms. Early sluice boxes consisted of long wooden boxes with wooden riffles and moss or burlap to line the bottom. The primitive long toms saved a ton of labour but miners at that time did not have a pre-scrubber and had to pick all the rocks out by hand and pan all the concentrates.

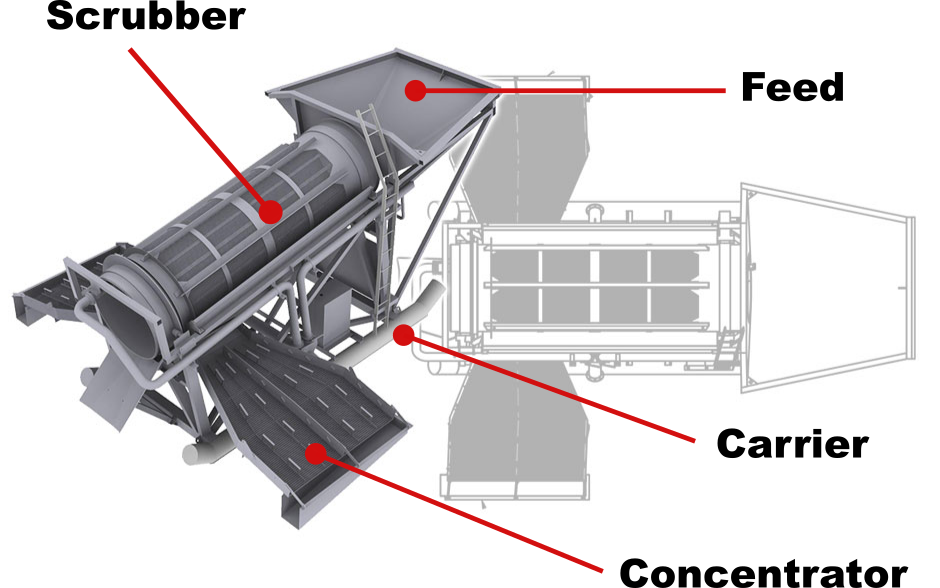

Modern sluices haven’t changed that much from the original design. We use metal now and have scientific studies to analyze the optimal riffle designs and matting but the concept is exactly the same.

Sluices work by creating a vortex behind the riffles. As the gravel/water slurry flows over the riffle it creates an eddy current as it rolls back on the riffle. The eddy causes the water to momentarily lose inertia and it can no longer carry the dense sediment. Dense material is held in the riffle as long as the water is flowing. Once the water stops, the suspended material is released from the riffles, that’s why it’s not good to stop and start a sluice box.

There are a variety of riffles in use today but they all work the same way. There have been some excellent studies on different riffle designs and matting.

- A study of the fine gold recovery of selected sluice box configurations, Jamie Hamilton at UBC: download PDF

- Placer Gold Recovery Research by Rany Clarkson of New Era Engineering: download PDF

Studies show which riffle designs work the best, what spacing between riffles is optimal and what angle to run at, typically 1.5 to 2.5 inches/foot of sluice run.

There are several different types of riffles in use today. The Hungarian riffle and expanded metal are most common in commercial sluicing operations. Miners in New Zealand developed the hydraulic riffle in the 90’s that allows water to inject under the riffle which keeps them from packing. It’s similar to the way that the Knelson concentrator uses a fluidized bed, more on that later in this article.

Some modern designs have abandoned riffles altogether and use a drop riffle or vortex such as the Devin Sluice or Dream Mat. These vortex systems catch gold in spirals carved into the matting or machined into aluminum sheets. Vortex riffles and matting have the advantage of quick clean-ups but they tend to work better on small-scale operations and clean-up sluices.

Different types of matting are used to catch fine gold. Miner’s moss is a typical matting that is made of a synthetic material with lots of loops to catch gold. Miner’s moss is kind of like a thick version of the soft side of velcro or thick carpet. Actual carpet is used in some cases as well. There are lots of high tech rubber designs on the market such as Gold Cube matting, Gold Hog, Dream Mat and many other designs. Some matting is easier to clean up than others but they all catch gold.

Other variations on the sluice include the live bottom and oscillating sluices. The live bottom box works really well. The live bottom box uses a thick rubber sheet on the bottom of the sluice box and has mechanized rollers that sort of massage the rubber moving it up and down. Similar to the rollers in a massage chair. That keeps the material from packing up and keeps the gold at the bottom.

Sluice boxes can handle huge scale production, they can be made very large and multiple sluices can be run together to handle even higher production. The largest wash plants in the world run multiple sluices. All sluices require careful setup and lots of tweaking to make sure they’re catching all the gold. Sluice riffles will eventually become packed with black sand and can no longer catch gold, for this reason, a sluice must be cleaned out regularly.

Despite the ubiquity of sluices and their simplicity an alarming number of commercial miners are losing fine gold off the end of their sluice. Quality control and testing is essential to make sure that your sluice is operating as it should be. A full-scale sluice can reliably capture gold down to 150 mesh with proper setup.

Sluices have the major disadvantage of slow cleanup times that require a full shutdown. They also lose gold when you start and stop the slurry feed. They are simple and easy to repair in the field though.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Can handle large volume | Proper setup is critical |

| Simple design, easy to fix in the field | Require shut down for cleanup |

| Modifications and adjustments are easy | Large footprint on commercial operations |

| Require frequent cleanups |

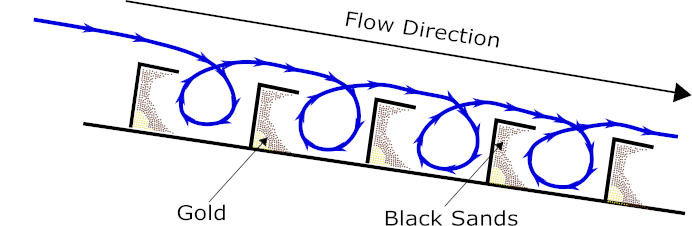

Hydrostatic Jigs

Hydrostatic Jigs, often just called “jigs” are very different than a sluice. They use a pulsating water action to separate gold from the lighter gangue materials. Jigs have serval components that work together to separate gold. Typically they have a screen in the upper section which holds a layer of steel balls called “ragging”, usually about 3” thick. Below the screen and ragging is a rubber diaphragm that is moved up and down rapidly by mechanical means producing a vertical pulsing action. The feed material flows over the screen is allowed to settle into the ragging.

The pulsing action in combination with the steel shot allows dense materials to settle to the bottom while lighter material is forced up and carried away by the flow. The action of the jig is based on Stokes Law which determines the rate at which particles fall while suspended in a fluid based on their density. Jigs are usually arranged in a series of cells, each with its own screen and diaphragm. Any number of cells can be used in combination to increase capacity.

The gold is stored in a container in the bottom called a “hutch”. One advantage to this system in commercial operations is that gold nuggets and pickers are not sitting in the open as they would be in a sluice box so it would be difficult for an employee to steal the gold.

Jigs first came into use in placer mining in 1914 in California. They were soon adopted to the large floating dredges that were in use at the time. Jigs had several advantages over sluice boxes. First, they take up much less space, which was important on a floating dredge. Secondly, they can be cleaned out without having to shut down the operation. You simply need to drain out the hutch and you’re back in business.

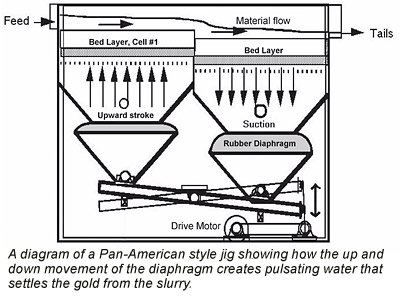

One of the first jigs used in placer mining was the Pan American Jig wich consisted of two cells. The Pan American model had two 42-inch square cells and could process 20 yards per hour. Multiple units were used in tandem to increase capacity.

Many modern jigs follow the exact same design as the Pan American. Many manufacturers around the world still produce an almost identical machine. There are many variations of jigs today but they allow work on the same principle. Smaller jigs are often used for cleaning concentrates but larger units are also used in full-scale commercial operations.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Clean up without shutting down | Initial setup requires lots of tweaking |

| Small Footprint | Rubber diaphragm wears out |

| Gold stored in safe container | Low capacity per cell |

| Dummy proof once set up | Specialised parts required |

Centrifugal Concentrator

Centrifugal concentrators are the most efficient method for concentrating placer gold in terms of capturing fine gold and overall revocery. They rely on a rotating drum that resembles a washing machine. The drum spins at high RPM, usually at least 100 RPM, creating a centrifugal force that pushes heavy elements to the outer edge. If you’ve ever ridden the gravitron ride at an amusement park you’ll know firsthand how this works.

In a centrifugal concentrator, the lighter material is allowed to flow over the top of the bowl and is discharged as tailings, the dense material is held in riffles and retrieved during cleanup. The principle is similar to a hydrostatic jig except more G forces are applied. At high G forces centrifuges are less sensitive to particle size than other gravity methods (sluice, jig, etc) and as such can retrieve extremely small gold grains down to 400 mesh.

There are four types of centrifugal processors on the market today: the Knudsen Concentrator, Falcon Concentrator, Knelson Concentrator, and the Gold Kacha.

The Knudsen was the first centrifugal concentrator used in placer mining. It was invented by George Knudsen of California and patented in 1942. The Ainlay bowl was patented in 1928 and saw some experiments in placer mining but didn’t take off. The Knudsen bowl is a 12” to 36” diameter bowl mounted on a vertical drive shaft. The bowl is tapered to allow the slurry to rise up the side while the riffles catch the gold. The Knudsen bowl was used all over the world most notably in California, New Zealand and in Africa. The Neffco Bowl is a modern version and is still used today.

The Knelson Concentrator was developed in Burnaby, BC in 1980. The Knelson is a bit more complex than the Knudsen Bowl and runs at a higher RPM. The Knelson concentrator uses a perforated cone and uses pressurized water that forces in from the outside of the bowl. The cone experiences a force of 60G’s while the water pushes against it, the counteracting force acts to keep the heavy particles fluidized allowing a continual replacement of light grains by heavy ones and avoiding the compaction of riffles like you see in a sluice. The Knelson concentrator is very efficient but like all centrifugal concentrators it requires frequent cleanups.

Falcon concentrators are similar to the Knelson. The main difference is the angle of the walls. Both use the same water pressure system that pushes against the centrifugal force creating a fluidized bed. Falcon (now called Sepro Mineral Processing) is based in Langley, BC, and was founded in 1987. It’s interesting that both Knelson and Falcon were developed in Greater Vancouver. Both companies are world leaders in mineral processing technology.

The Gold Kacha (GK) is a really cool system. I was introduced to this device on a recent placer exploration trip to Sierra Leone, Africa. The Gold Kacha was developed in 2005 in South Africa by Appropriate Process Technologies (APT). It’s similar to the Knudson/Neffco bowl but has several advantages. The Gold Kacha can easily process gold down to 450 mesh (30 microns) and the riffles are designed to prevent gold compaction. The GK can run 3-4 cubic yards per hour.

It’s set up in a turnkey package that’s easy to use. The biggest advantage is that the Gold Kacha retails for $1,500 USD. All the other concentrators on this list are at least 4 times that cost but the GK was designed for use in third world Africa to help artisanal miners avoid using mercury.

All centrifugal gold processing machines work well for catching very fine gold, they catch coarse gold too but the fine gold is the challenging part. Centrifugal processors can catch extremely fine gold very well but they require frequent cleanups, usually every hour or so. Some wash plants use multiple centrifuges and are able to isolate them using valves so that while one centrifuge is being cleaned the others are still operational, I think we’ll see more of these systems in years to come.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Able to retrieve gold < 400 mesh | Frequent cleanups are required |

| Easy to use, no special knowledge required | Very expensive (except Gold Kacha) |

| Low water consumption | Low capacity per unit (compared to sluice) |

| Low power/fuel consumption | Requires thorough pre-screening and clean water |

Spiral Concentrators

Spiral concentrators are not commonly seen at placer mines these days. They were popular in the 70s and 80s but have fallen out of fashion. They are very commonly used in the beneficiation of heavy mineral sands, chromite, tantalite, iron ores and fine coal.

Basically, spiral concentration involves a stack of spirals that are fed from the top using a low-pressure slurry pump. The slurry flows down the spirals like a water slide and separates based on density. At the bottom there are splitters that divert the slurry at different points along the radius of the spiral. The outside of the spiral will have the tailings, since they are less dense the spiral action forces them to the outside, the concentrated gold is on the inner radius and the “middlings” are in the middle. The principle is similar to the way that a shaker or wave table separates gold.

Spirals are often run several times so that the middlings can be run again to increase their level of concentration. There are several variations such as the pinched sluice and the Reichert Cone which uses a series of stacked cones instead of spirals. The spirals are usually made of fiberglass and are lightweight and fairly inexpensive. They are able to reliable capture gold from 6 to 200 mesh, some models can catch down to 300 mesh. Placer spiral systems can handle 4-10 yards per hour but can be scaled up with more units.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Able to retrieve gold < 300 mesh | Require consistent, laminar flow |

| Easy to use, no special knowledge required | Low capacity per unit (compared to sluice) |

| Low cost and cheap to operate | Requires thorough pre-screening |

| Low power/fuel consumption |

Dry Washers

Gold is found in areas that don’t have water available, such as the desert regions of California, Nevada, Arizona, and Australia. Placer miners came up with a solution for dry washing.

The process works on the principle of winnowing, which uses wind or air to separate dense material from less dense material. The technique has been used for millennia to separate grains from their husks. Dry washers use a short, waterless sluice and pressurized air in combination with vibration. The sluice portion of a dryswasher has a porous bottom, either canvas or a very fine screen, that allows air to pass through. The whole thing is set on a steep angle so that the material can work its way over the riffles. Air blows up from the bottom and provides some buoyancy for lighter material.

Small scale dry washers resemble a highbanker with a screen/grizzly on the upper section and a sluice-like screen setup on the bottom. There are hand-operated units using bellows, and gas-powered blowers. Commercial-scale drywasers are somewhat rare but they are used in gold-rich areas of Australia and parts of the United States.

There are no manufacturers that make commercial-scale dry washers. All large scale units are custom made. Most of them are fed by a loader and distribute the material through a screen system into multiple cells of smaller dry washer sluices. Keene is developing a commercial drywasher but it’s not available at this time.

Material to be run in a drywasher must be completely dry, it must contain less than 3% water otherwise it won’t work. The material must also be disintegrated and not clumped together by clay or caliche. Studies show that under ideal conditions a dry washer will have about 15% less recovery than a wet system (ie. sluice).

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Doesn’t require water | Lower recovery than wet systems |

| Can be moved rapidly | Makes a lot of dust |

| Fast cleanup (compared to wet sluice) | Frequent cleanups are required |

Feed Systems

We’ve covered screening systems and concentrators. The next component of a wash plant is the feed system. Wash plants can be fed in different ways. Some have a hopper that is fed by an excavator or loader, others are fed by a slurry pump or dredge.

Hoppers

The most common feed system on a wash plant is the hopper. The hopper is a large container that is filled with raw gravel and allows it to be dispersed at an even rate. Many hoppers are gravity-fed, they operate in a similar way to an hourglass. They have an inverted pyramid shape and act as a funnel.

Other hoppers have a belt or track in the bottom that manages the feed rate. I’ve seen some cool designs in the Yukon that use a recycled excavator track in the bottom of the hopper to slowly feed a trommel.

The hopper won’t feed itself and must be refilled regularly by an operator. Most operations either use an excavator or a front end loader to keep the hopper full. Some miners use a conveyor belt system in combination with a hopper to maintain an even flow of material.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Maintain even flow (when not clogged) | Large rocks can get stuck |

| Simple design, not much to break down | Requires operator to refill regularly |

Bucket Ladder

The bucket ladder is the most efficient system for feeding wash plant. This was the norm on the monster floating dredges that scoured the gold-bearing placers of western North America from the late 1800s till the 1950s. These monster dredges moved ridiculous amounts of gravel, each dredge could efficiently process up to nine tons of gravel per minute, with an average of 20,000 cubic yards per day!

The bucket ladder consists of a boom and a series of metal digging buckets. It’s sort of like a giant chainsaw. The buckets are specially designed with a digging edge and held together with a giant chain. The boom is raised up and down with a gantry winch system. The buckets continually dump material into the scrubber system (trommel, screen deck or any other system that we discussed above).

The depth of the bucket line is limited to the length of the boom. Typical industrial dredges could dig up to 60 feet deep. The buckets are able to dig up soft bedrock but if hard rock is encountered they cannot. The buckets can’t handle large boulders either. The dredge in the video below isn’t at a placer mine but it shows what a modern bucket ladder dredge can do.

Environmental restrictions have made it a lot more difficult to operate a floating plant with a bucket line but some are still in operation today in Europe, Africa, Russia, China, Asia, South America, Mexico and the Yukon. Modern bucket ladder dredges are common in non-placer applications

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Constant supply of material | Can’t dig too deep |

| Huge capacity | Massive overhead cost |

| Excavation and delivery in one step | Not very mobile |

| Few breakdowns | Regulatory hurdles |

Gravel Pump

One of the most efficient ways to feed a wash plant is with a gavel or slurry pump. There are several large-scale placer mines in Alaska and other parts of the world that mine by hydraulic means using large water monitors. The material is washed into a pit and pumped up to the wash plant using large industrial slurry pumps.

Gravel pumps don’t work in every scenario but if your location is favorable this is a very efficient way to mine. The slurry pump can be unmanned, saving labour costs and allowing workers to focus on other areas of the mine. These pumps are very expensive initially but the savings in operating costs will pay off over time.

There are a lot of mines operating in wet ground in BC and the Yukon and a slurry pump would be an excellent solution. Instead of fighting the groundwater you can use it to your advantage.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Consistent feed of material | High initial cost |

| High capacity | Requires careful mine planning |

| Savings on labour | Doesn’t work in every location |

| Good solution for wet ground | Possible regulatory hurdles |

Suction Dredge

Suction dredges are similar to a slurry pump set up. A suction dredge uses a venturi to create a vacuum that sucks up gravel and water at the same time. Floating dredges are commonly used in small to mid-scale mining. Floating dredges are classified by the diameter of the suction hose which varies from 3 to 8 inches.

Modern suction dredges first became popular in the 1950s due to the availability of good, portable, centrifugal water pumps and modern diving equipment. Some jurisdictions such as British Columbia and parts of California have banned suction dredging but it is a very efficient method that is used around the world.

There are some very advanced dredge machines on the market today. Large scale operations are using 8-inch and larger suction lines. Some of the most interesting dredge innovations are being developed for use on the Bearing Sea in Alaska. The robot dredge in the picture below is a really cool new technology that uses a remotely operated robot with a cutting head attached to an 8-inch dredge.

Not all dredge systems use a floating platform and can be fitted to just about any wash plant. You can get excavator-mounted units up to 12” in diameter that can be used in a regular mining pit. These systems advertise up to 600 cubic yards per hour of production.

Some systems use slurry pumps instead of a venturi in combination with a cutting head. The advent of undersea mining has pushed the envelope on this technology and we’re going to see a lot of advancements in the coming years.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Consistent feed of material | Doesn’t work in every location |

| Excavation and feed at the same time | Possible regulatory hurdles |

| Can be unmanned |

Wash Plant Carriers

This is the part of the washplant that supports the scrubber, concentrator, and feed system.

Stationary Skids

Many large wash plants are mounted on a steel frame welded to metal skids. This system isn’t very mobile. Skid-mounted plants are meant to stay in one place for a long time. When it’s time to move they are pulled by heavy equipment such as bulldozers or large excavators and dragged into position.

Skids are simple and stable but don’t provide a lot of mobility.

Trailer or Frame with Wheels

Small to mid-sized wash plants can be mounted on a trailer or frame with wheels. This provides an easy way to move it around. The trailer will often have a leveling apparatus to stabilize the plant while in use. Not much else to say, it’s a trailer we all know what that is.

Floater Plant

The floater plant, also known as a “Doodlebug” is a very efficient way to mine. The plant can be mounted on pontoons or a barge. Floater plants have the ability to move very rapidly in a pond of their own making. It takes planning to operate efficiently without boxing yourself in but when properly executed a floater setup can move a lot of material quickly.

Any type of scrubber, concentrator, and feed system can be fitted onto a floater.

The large bucket line dredges technically fall into this category but most floaters today use an excavator to dig and pull the barge. For a floater operation to work effectively the ground can’t be too deep. Floaters mine in one continuous direction mining in front of the plant while the tailings are deposited behind. It’s almost like an assembly line approach to placer mining.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Rapid movement | Don’t work in deep ground |

| Efficient mining and tailings management | Require a pond for the plant to float on |

A placer wash plant is the sum of its parts. It’s not a trommel, it’s not a sluice, it’s the whole package. There are just about as many combinations as there are miners. Placer miners are always coming up with new innovations to solve problems and mine more efficiently.

There is no one plant that is the best in every situation. They all have their strengths and their weaknesses. The type and size of your gold, the type of gravels you’re dealing with, ground conditions, regulatory environment, available capital, and other factors all work together to determine what type of wash plant is best for your mining operation.