As prospectors, we have a deep connection to the past. We live in a world where technology has advanced to an amazing level. High tech devices that could only be imagined by science fiction authors a few decades ago are part of our everyday lives. Despite the current state of technological advancement, there is still no surefire way to detect unexplored gold deposits. Our pursuit of the yellow metal leaves no stone unturned. A good prospector will employ every tool at their disposal to get even the slightest edge in locating a gold deposit.

We look to the prospectors of the past and admire their ability to locate gold deposits with nothing more than their own ingenuity and a sense of adventure. Some techniques are no longer used and some haven’t changed for centuries. Dowsing fits somewhere in between. It’s always been a mystery. Nobody can explain how it works but many swear on their mother’s grave that it does.

Dowsing refers to the practice of using a forked stick, metal rod, pendulum, or similar device to locate underground water, minerals, or other hidden or lost substances, and has been a subject of discussion and controversy for

hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The practice is also called divining or witching. There is a history of mysticism, magic, and supernatural beliefs associated with the divining rod that dates back over 8,000 years.

In the Tassili Caves of northern Africa, an 8,000-year-old cave painting depicts a man holding a forked stick, apparently using it to search for water.

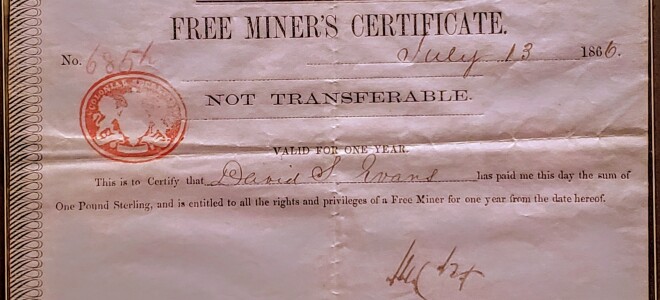

Divining rods were used by the Scythians, Persians, and Medes. The practice was used by Bavarian miners in the early 1500s and spread throughout Europe as their deep mining skills were highly sought after. Check out our article on Free Miners for a bit more info on that.

Controversy on the subject goes back to before medieval times. In 1518 Martin Luther listed the use of the divining rod as an act that broke the first commandment under the assumption that dowsing is in league with witchcraft. One of the most important books on mining during that period called “De Re Metallica”, published in 1556, describes the practice in this excerpt:

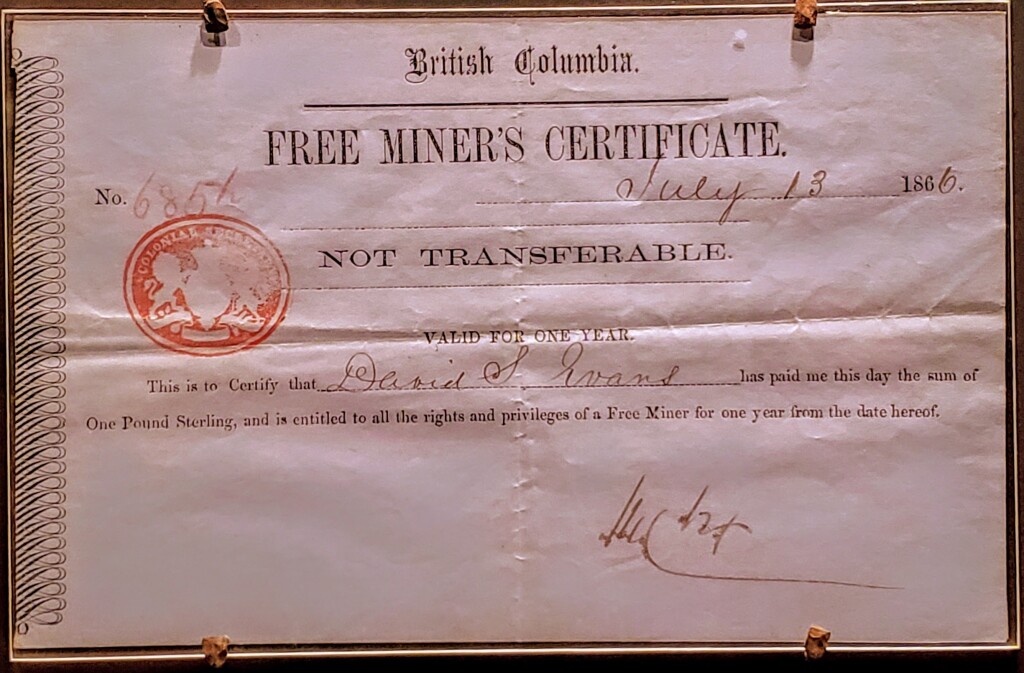

There are many great contentions between miners concerning the forked twig, for some say that it is of the greatest use in discovering veins, and others deny it. Some of those who manipulate and use the twig, first cut a fork from a hazel bush with a knife, for this bush they consider more efficacious than any other for revealing the veins, especially if the hazel bush grows above a vein.

Others use a different kind of twig for each metal when they are seeking to discover the veins, for they employ hazel twigs for veins of silver; ash twigs for copper; pitch pine for lead and especially tin, and rods made of iron and steel for gold. All alike grasp the forks of the twig with their hands, clenching their fists, it being necessary that the clenched fingers should be held toward the sky in order that the twig should be raised at that end where the two branches meet. Then they wander hither and thither at random through mountainous regions.

It is said that the moment they place their feet on a vein the twig immediately turns and twists, and so by its action discloses the vein; when they move their feet again and go away from that spot the twig becomes once more immobile.

Nevertheless, these things give rise to the faith among common miners that veins are discovered by the use of twigs, because whilst using these they do accidentally discover some; but it more often happens that they lose their labour, and although they might discover a vein, they become none the less exhausted in digging useless trenches than do the miners who prospect in an unfortunate locality.

Therefore a miner, since we think he ought to be a good and serious man, should not make use of an enchanted twig, because if he is prudent and skilled in the natural signs, he understands that a forked stick is of no use to him, for as I have said before, there are the natural indications of the veins which he can see for himself without the help of twigs.

There are variations on the construction of dowsing rods. The original technique consists of using a forked branch cut from a live tree, any tree will work but sticks from willows, witch hazel, and various fruit and nut trees seem to be the most popular. You grasp the ends of the “Y “in your hands with your palms facing upwards. The technique is to walk around and as you approach the target (ground water, gold deplost, etc) the rod will bend towards the ground.

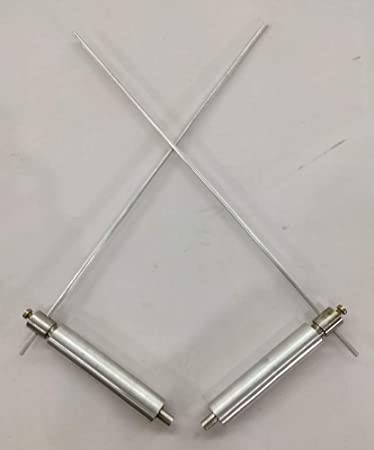

Modern dowsers prefer to use metal rods. A modern dowsing rod consists of two metal rods created from sixteen inch long steel acetylene welding rods with a 90 degree bend forming a handle on each (also known as L-rods). The latest innovation uses ball bearings in the handle to allow the rod to move freely. The modern divining rods don’t bend towards the ground, the technique is to allow the rods to either cross or reach the operator’s chest or point in certain directions.

There are people claiming to be able to conduct long-range dowsing from distances of 100s of meters up to thousands of kilometers away. Some even claim to be able to dowse using a map from the other side of the world.

Dowsers claim to be able to find all sorts of things ranging from water to gold and even your lost car keys. Dowsing for water is the most common. There are quite a few practitioners of water dowsing that do so as a career. The American Society of Dowsers currently has over 2000 members.

Personal Accounts

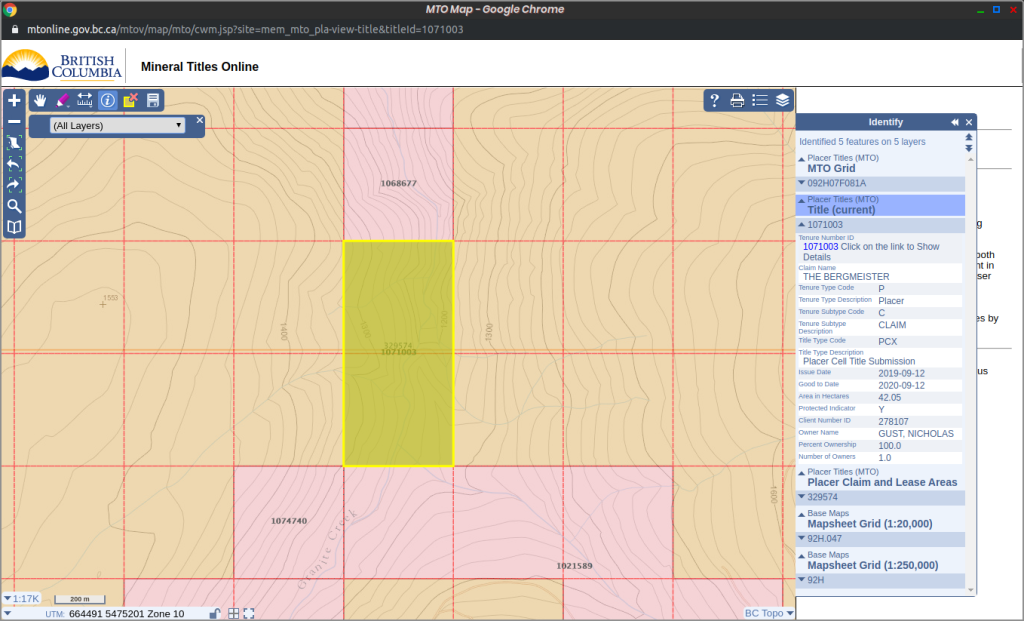

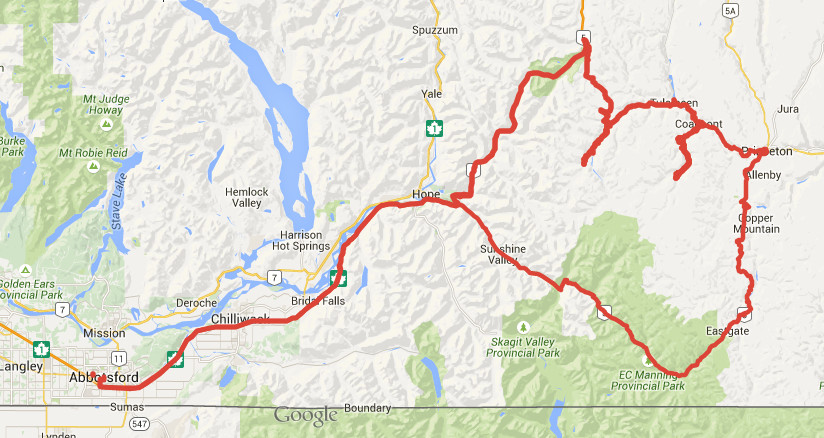

In the summer of 2020 I had the opportunity to try dowsing myself. A friend of mine had some dowsing rods and we gave it a try while exploring his claim. He told me that you need to visualize the thing that you’re looking for. In this case we were exploring for a hidden paleochannel.

I held the rods horizontally so that they were able to move freely and walked in a straight line while keeping the idea of a channel in my head. At one spot I was surprised to feel the rods moving without my control and they did cross in front of me. It was a cool feeling and did seem supernatural. We marked the spot using a pin flag. My friend continued over a larger area and we mapped several spots where he felt the rods cross. The results didn’t match up to our seismic survey but he will be testing the area with his excavator next summer.

My personal account was by no means a conclusive test. It certainly piqued my curiosity though.

I know several professionals that occasionally use the technique to locate underground utilities such as water lines and electrical lines. They swear that it works, they don’t know how or why but swear that it does. Several utility companies in Canada do use divining rods occasionally.

Long Range Locators

There are even electronic devices that claim to extend the dowsing signal for great distances. These devices are called Long Range Locators (LRLs).

There is quite a range of LRLs on the market, they range from devices that look like a ray gun to “signal generators”, “oscillators”, “harmonic molecular resonators”, or other scientific-sounding names. The world of LRLs is very murky. The majority of LRLs are fake and many manufacturers have been charged with fraud.

One such device called the Omni-Range Master retails for $2,885 USD and makes the following claim:

The signal line from the Omni-Range Master can scan an area of at least 64 square miles and determine if any of the sought-after mineral is present within 15 minutes of the start of operation

It also claims to have “Accuracy of 1/32 of an inch from 50 feet to over 8 miles”. Wow, it would be pretty cool if that actually worked!

Credit for the above photo goes to Carl at geotech1.com. He’s done a lot of research and testing on LRLs. Check out his site for some surprises on some of the most popular long-range locator products on the market.

The Omni-Range Master is a favorite among dowsing and LRL enthusiasts even though it doesn’t actually do anything.

The manufacturer supplies a list of frequencies to locate various substances and items such as:

- Diamonds – 12.835 Khz

- Gold – 3.025 Khz

- Titanium – 13.385 Khz

- “Prehistoric Rex” bones – 15.367 Khz

- Paper money ($100) – 9.41 Khz

- Paper money ($20) – 12.77 Khz

It’s interesting that it mentions bones of a non-existent dinosaur which would be made up of a complex mix of molecules. It’s also strange that it has two different frequencies for paper money and that it lists paper money at all.

This device uses a standard waveform generator (chip that produces an electrical current in a variety of voltages and frequencies). You then plug electrodes into the ground and the idea is that the device will induce “molecular resonance” in the surrounding area and create “signal lines” that you can follow with dowsing rods.

The device uses a 12V power supply and does not transmit enough power to do anything productive. I suspect that believers in “signal lines” and LRLs believe that a very low voltage can be amplified by a form of harmonic resonance but there is absolutely zero evidence for that.

At face value, the concept of “frequencies” and electrodes in the ground is similar to some geophysical techniques such as Induced Polarization (IP) and Resistivity that are commonly used. IP uses 25,000 volts and very specialized recording equipment. It also involves a comprehensive data processing technique. IP can detect conductive ore bodies if they are big enough but even that advanced geophysical technique won’t show you exactly where gold is (or dinosaur bones).

Explanations of the Phenomenon

Proponents of the dowsing technique have a variety of explanations of the mechanics behind the phenomena. One person on a prospecting forum recently claimed “The rods simply extend your personal magnetic field..which, in turn responds to, and interacts with vibrational frequencies of the Earth.”

Some claim that there is psychic energy involved while others say it has something to do with the solar cycle and charged particles from the sun. There are just about as many explanations as there are practitioners.

A recently published book, “The Art of Dowsing: Separating Science from Superstition” by Michael Fercik, tried to explain dowsing in scientific terms. Here’s a quote from the book:

The hands-on dowsing practices are absolutely 100 percent correct, but the dowsing theory could be slightly off here or there. I expressed in wording to the best of my abilities on how I can dowse to find sought objects, with the physics that came from electrical classes, a college physics class, educational books, and educational TV programming. If a group of open-minded physicists say one of the theories is not this way but is that way, then I stand corrected, and we go by the group of open-minded physicists’ theory.

The author seems to have a very faint understanding of science despite the fact that his book is titled “Separating Science from Superstition”.

Fercik explains his own theory of the concept of “elemental magnetism”. It’s important to clarify what the word “theory” means in the realm of science. People often claim something is “just a theory” or “I have a theory”. That word has a specific meaning in science. A scientific theory is an explanation of the natural world that makes testable and verifiable predictions. Those predictions must be confirmed by experiments using the scientific method. You can’t have a theory without it being able to make predictions that can be verified by other people, otherwise it’s just a guess and doesn’t have anything to do with science.

Fercik goes on to explain that each element in the periodic table has its own unique “elemental magnetism” and that a dowsing rod can “tune in” to that unique characteristic similar to a radio tuning to a radio station. He claims that you can tune in your rod by attaching a “one-tenth troy ounce” piece of silver, for example. Then your rod is tuned for silver. He emphasizes that it must be 99.999 percent pure silver or gold or else it won’t work.

The author claims that a dowsing rod and metal detector work in similar ways and that the dowsing rod is powered by “human neuron electrical signals”. Apparently walking while dowsing builds up a static charge strong enough to move the rods when your target is close.

Fercik claims that metal detectors and dowsing rods both work by “picking up the unique emitted elemental magnetic flux lines of the targeted element or targeted elemental mass.” In reality neither device works that way.

Metal detectors transmit an electromagnetic field from the search coil and any magnetically susceptible metal objects that are close enough and large enough become energized and retransmit their own field. A second coil receives the field transmitted by the metal objects. It’s a similar concept to electromagnetic geophysics such as HLEM or aerial TEM. Modern metal detectors are able to differentiate certain phase responses and that allows them to discriminate between different metals such as gold and iron. When metals have a similar phase response such as tin foil and gold it’s hard to tell the difference.

The author describes the movement of the dowsing rod as the result of closing a circuit and allowing static electricity to flow. According to the book, when in contact with the sought element’s “elemental magnetic flux lines” a circuit is created and the dowsing rod connects the static electricity of the human body’s nervous system with the “elemental flux density” of the sought element.

The author goes on to introduce numerous other terms related to magnetism that he created from his own imagination. His ideas don’t meet the criteria for a scientific theory, they could be easily tested but there is no evidence of that in the book. He also fails to recognize that water is not made of a single element, it’s composed of hydrogen and oxygen.

The author should have consulted someone with a background in physics or chemistry instead of his emphasis on “educational TV programming”. Scientists aren’t hard to find, however, had he done that there wouldn’t be a book to write since it would have been debunked before it even reached the publisher.

Ideomotor Effect

Dowsing rods have been shown to work on the same principle as a Ouiju board. The rods, or the planchette in the case of the Ouija board, are moved by human muscles not ghosts, magic or “elemental magnetic flux lines.” The reason the operator isn’t aware that they are actually moving the object is what’s referred to as the ideomotor effect.

The ideomotor effect was discovered by William Benjamin Carpenter in 1852 and describes the movement of the human body that is not initiated by the conscious mind. Your body moves without requiring conscious decisions all the time. In sports it’s referred to as muscle memory. Driving a car is another example, or playing a musical instrument.

When you are startled or accidentally touch something hot your body is able to move in a way to protect you without conscious input from your brain. Many experiments have shown that under a variety of circumstances, our muscles will behave unconsciously in accordance with an implanted expectation. As this is happening we are not aware that we ourselves are the source of the resulting action.

One of the first people to study this effect was the famous scientist Michael Faraday who also established the basis for the concept of the electromagnetic field in physics among many of his important contributions to the world of science. During the time of Faraday’s ideomotor experiment, in 1853, mysticism was at an all time high and Ouija boards were very popular. He set out to determine what the real force behind the Ouija board was.

Faraday’s experiment was simple. He placed a small stack of cards on top of the Ouija planchette (the piece that you put your hands on). In this experiment, if the force was coming from the participant’s hands the top of the deck of cards would move first. If there was another force the bottom cards would move first. What Faraday and others have shown in every case is that the force was coming from the participant’s hands and not some external entity.

Modern experiments have been done to test dowsing using high-speed cameras. It has been shown that the force on the dowsing rods comes from the person and not from an external force.

It’s interesting that today’s purveyors of the technique insist that testing needs to be done by “open-minded” scientists as if there is some kind of conspiracy against dowsing. There is no conspiracy, in fact there have been a lot of scientific experiments conducted to test the dowsing.

Take a look at some of the studies mentioned below. This is by no means a comprehensive list, there are hundreds of studies on this subject.

Chris French 2007

Psychologist Chris French conducted a double-blind study on dowsing in 2007. The study was filmed as part of a TV show hosted by Richard Dawkins.

Professor French had this to say about the dowsing experts that took part in the study:

I think that they are completely sincere, and that they’re typically very surprised when we run them through a series of trials and actually say, at the end of the day, “Well your performance is no better than we would expect just on the basis of guess work.” And then what typically happens, they’ll make up all kinds of reasons, some might say excuses, as to why they didn’t pass that particular test.

Ongley, P., 1948

Ongley tested 75 professional water diviners in New Zealand in 1948. The report, linked above, is quite interesting, it discusses some of the history and methods available at the time.

Ongley concluded, “If the seventy-five diviners tested representative of all occupations and from all parts of New Zealand, not one showed the slightest accuracy in any branch of divination. That 90 percent of the diviners are sincere does not lessen the harm that they do.

Vogt, E & Hyman, R, 1959

Water Witching, U. S. A.

Vogt and Hyman argue at some length that anecdotal evidence does not constitute rigorous scientific proof of the effectiveness of dowsing. The authors examined many controlled studies of dowsing for water, and found that none of them showed better than chance results.

Taylor, J. G. & Balanovski, E., 1978

Can electromagnetism account for extra-sensory phenomena?

In this study John Taylor and colleagues conducted a series of experiments designed to detect unusual electromagnetic fields detected by dowsing practitioners. They did not detect any.

Foulkes, R. A, 1971

Dowsing Experiments

Experiments organized by the British Army and Ministry of Defence suggest that results obtained by dowsing are no more reliable than a series of guesses.

McCarney, R et al, 2012

This study took place in 2012 and studied a different part of the dowsing technique. The study states: “According to the theory of psionic medicine, every living thing and inanimate object is continuously vibrating at a molecular level. This vibration is sensed subconsciously by the dowser, and it is then amplified through the pendulum or other dowsing device.”

Participants were tested on their ability to detect naturopathic medicine vs a placebo in double blind trials. The study showed that the experienced dowsers were not able to identify the correct substance with results better than chance alone.

Grave Dowsing Reconsidered

This study is a review of previous experiments which was put together by the office of the state archaeologist at the University of Iowa. The study concluded:

Simple experiments demonstrate that dowsing wires will cross when the dowser observes something of interest; this is an example of the subconscious ideomotor effect, first described by Carpenter (1852). This does not disprove dowsing, but demonstrates that simpler explanations can account for the phenomena observed by dowsers The premise that dowsing rods cross when exposed to a large magnetic field created by a subsurface anomaly runs contrary to basic scientific understanding of magnetic fields, and does not hold up under simple experiment.

One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge

The One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge is an offer by James Randi, a famous magician, to anyone who could demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal ability under agreed-upon scientific testing criteria.

In his book, “Flim-Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns, and Other Delusions”, Randi describes one of the tests that he conducted in 1979 where four dowsers took an attempt at the prize.

The prize in 1979 was $10,000 and he accepted four people to be tested for their dowsing ability in Italy. The conditions were that a 10 meter by 10 meter test area would be used. There would be a water supply and a reservoir just outside the test area. There would be three plastic pipes running underground from the source to the reservoir along different concealed paths. Each pipe would pass through the test area by entering at some point on an edge and exiting at some point on an edge. A pipe would not cross itself but it might cross others. The pipes were 3 centimeters in diameter and were buried 50 centimeters below ground.

Valves would select which of the pipes water was running through, and only one would be selected at a time. At least 5 liters per second of water would flow through the selected pipe. The dowser must first check the area to see if there is any natural water or anything else that would interfere with the test, and that would be marked. Additionally, the dowser must demonstrate that the dowsing reaction works on an exposed pipe with the water running. Then one of the three pipes would be selected randomly for each trial. The dowser would place ten to one hundred pegs in the ground along the path he or she traces as the path of the active pipe. Two-thirds of the pegs placed by the dowser must be within 10 centimeters of the center of the pipe being traced for the trial to be a success. Three trials would be done for the test of each dowser and the dowser must pass two of the three trials to pass the test.

A lawyer was present, in possession of Randi’s $10,000 check. If a claimant were successful, the lawyer would give him the check. If none were successful, the check would be returned to Randi.

All of the dowsers agreed with the conditions of the test and stated that they felt able to perform the test that day and that the water flow was sufficient. Before the test they were asked how sure they were that they would succeed. All said either “99 percent” or “100 percent” certain”. They were asked what they would conclude if the water flow was 90 degrees from what they thought it was and all said that it was impossible. After the test they were asked how confident they were that they had passed the test. Three answered “100 percent” and one answered that he had not completed the test.

When all of the tests were over and the location of the pipes was revealed, none of the dowsers had passed the test. Dr. Borga had placed his markers carefully, but the nearest was a full 8 feet from the water pipe. Borga said, “We are lost”, but within two minutes he started blaming his failure on many things such as sunspots and geomagnetic variables. Two of the dowsers thought they had found natural water before the test started, but disagreed with each other about where it was, as well as with the ones who found no natural water.

Cargo Cult Science

Dowsing has never actually passed any real scientific test. That has nothing to do with how “open minded” the scientists doing the study are. Science does not rely on opinion, it’s simply an unbiased way of testing and explaining the natural world. True science does not try to prove a hypothesis, a real scientist should try their best to disprove the hypothesis and only when all attempts to disprove it have failed can we draw the conclusion that the phenomenon is true.

The famous physicist , Richard Feynman, described this perfectly in his 1974 commencement address to the graduating class of Caltech. It’s a great speech that touches on pseudoscience and cargo cults. Check out the video below.

Dowsing is a pseudoscience, at best, and attempts to explain dowsing would definitely fit into Feynman’s description of Cargo Cult Science.

It would be amazing if a prospector could actually pick up two metal rods and walk around until they find a high-grade gold deposit. The idea is very appealing, and that desire is what has kept it around for so many years. If that actually did work, everyone would be able to find gold in large quantities and the practitioners of dowsing would all be multi-billionaires.

Even if you ignore the scientific studies and everything else mentioned in this article it’s pretty obvious that the practitioners of dowsing have failed the fundamental logic test. If they have the magical ability to find gold by holding two rods, shouldn’t they have tons of gold in their possession?

I have had long conversations with numerous expert dowsers. Except for a few that get paid to dowse for water, they all have a day job and dowse as a hobby. Dowsers all swear that the technique works and is effective but they don’t have any gold to show for it. I have yet to meet a dowser that has discovered billions of dollars worth of gold and lives in a mansion.

It is possible that there is some hidden force that we don’t yet understand that can be tapped into using the human body and two metal rods. That’s the idea promoted by dowsing practitioners. They claim there are unexplained “frequencies”, “harmonic molecular resonance”, “elemental magnetism” or other clever-sounding phrases that science hasn’t yet been able to explain.

Dowsing, like many other forms of divination or intuitive practices, can tap into a person’s beliefs about the nature of reality, the power of the mind, and the existence of unseen forces or energies. For some individuals, the act of dowsing may feel like a sacred or meaningful practice that connects them to something greater than themselves. This sense of connection or spirituality may contribute to their confidence in their abilities, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Additionally, the social dynamics of a community of dowsers may also contribute to their confidence in their abilities. If a person is part of a group that strongly believes in dowsing, they may feel more confident in their own abilities due to the collective reinforcement of their beliefs. This social reinforcement can create a sense of community and belonging that reinforces the belief in dowsing as a valid and effective practice.

Carl Sagan famously stated, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” The claims made by dowsers are certainly extraordinary. The extraordinary evidence has yet to present itself.

If you’re waiting for the discovery of a magical force that presents signal lines to buried gold that only a specialized few are able to pick up on with their innate abilities, I wouldn’t hold your breath. It’s far more likely that the phenomenon of dowsing is little more than a self-delusion brought on by unconscious movements in response to implanted expectations, also known as the ideomotor response.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and personal dowsing stories. Feel free to post them in the comments below.