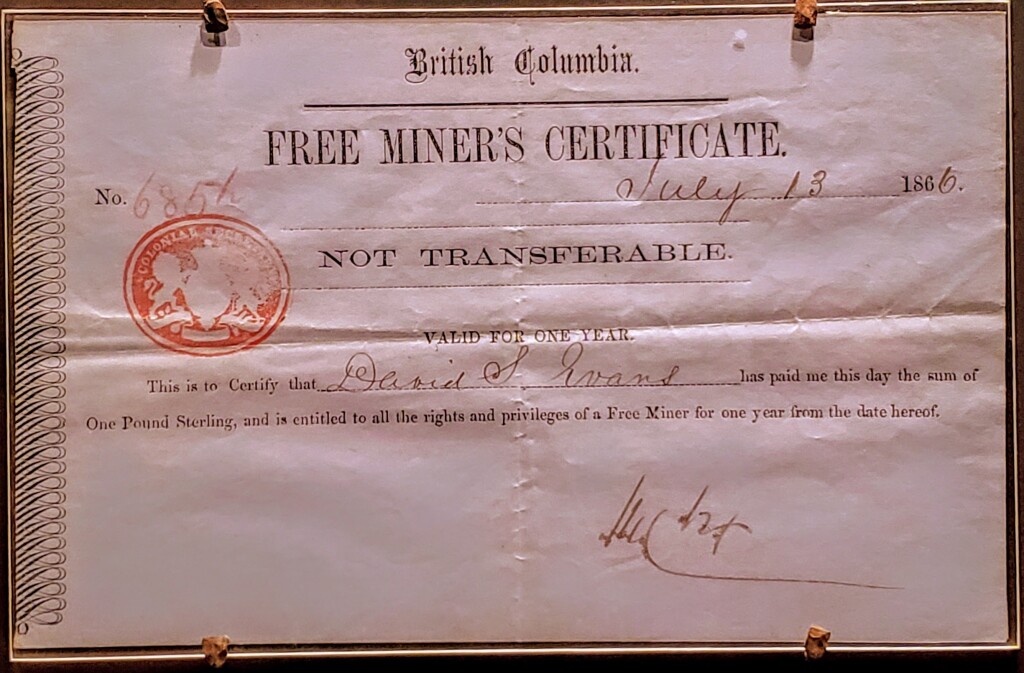

In British Columbia it is necessary to hold a Free Miner’s Certificate (or FMC for short) to buy and sell mining claims. Most miners, prospectors and industry professionals hold an FMC but do they know what it stands for? The concept of the Free Miner holds historical roots dating back to medieval Europe where being a free miner meant a certain status and freedom during a time when freedom was reserved for a select few.

Mining law in BC dates back to before British Columbia even existed. Few British Columbians actually know the history and genesis of this beautiful province. We talk about the fur traders and explorers like Simon Fraser, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, and David Thompson. To this day they are credited with “discovering” BC. Their names are on our streets, our rivers, and countless monuments around the province.

The early explorers definitely laid the groundwork for things to come but it wasn’t until word got out about a peculiar yellow metal that things really got rolling. Once word reached California about gold in the Fraser Canyon the rush was on. Modern-day BC consisted of a disputed territory called New Caledonia during the time of the gold rush.

The mining law in BC was modeled after regulations in other British colonies such as Australia and New Zealand. The underlying principles of our mining laws date back to medieval Europe with a history dating all the way to the Roman Empire.

Beginnings of the Free Miner

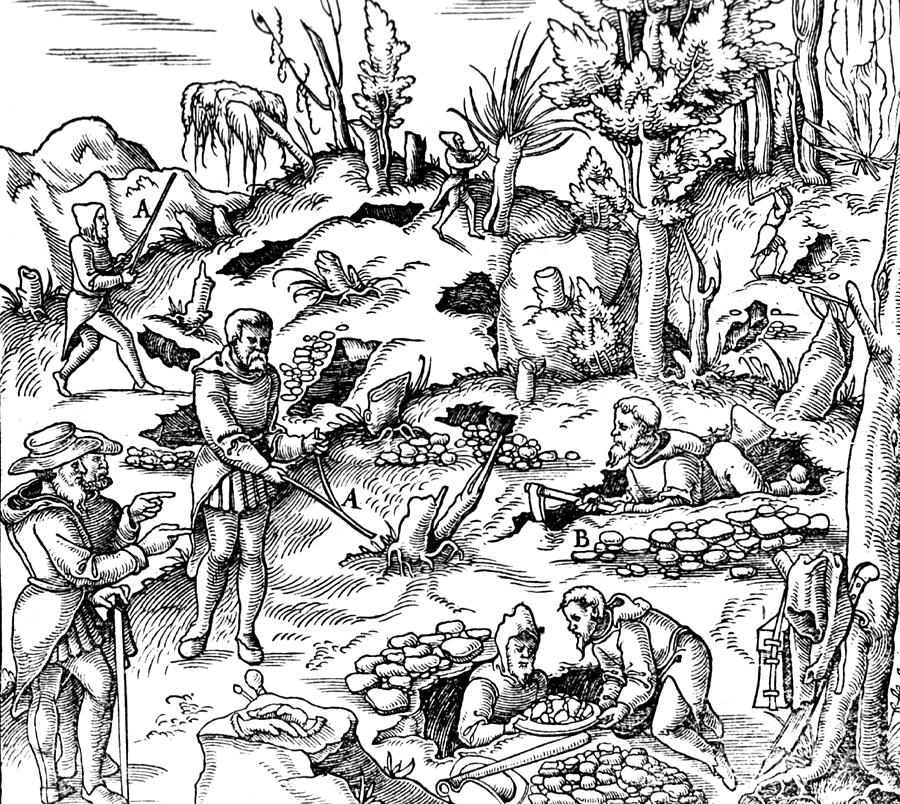

Work in mines during the time of the Greek and Roman empires was primarily conducted by slaves and prisoners. The Romans were producing gold and silver coins used as currency and required more precious metals than were being produced by traditional mines. During the reign of Emperor Charlemagne (768-814) the demand for gold and silver increased. The easily exploitable deposits were beginning to run out and there was a need for specialized mining skills and knowledge.

The Romans recognized the prospecting skills that miners possessed and began to allow slaves and peasants the freedom to explore. The Romans created the right to ownership based on discovery where if a man discovered a mineral deposit he could claim ownership. It was required that he pay a royalty or tribute to the emperor. Through this process, the miner ceased to be a serf and became a free man.

The incentive of freedom drove men to the farthest reaches of the Roman empire in search of metals and subsequently their own freedom. The adventurers taking part in the gold rushes of the 1800s in North America were driven by the same force, to find freedom and wealth on their own terms. The right to discovery has always been one of the core tenents of the free miner system.

Medieval Europe

During the middle ages land was owned outright by lords. Lords were subject to the king but they decided what would and wouldn’t happen on their land. The land was worked by peasants who owed a certain amount of workdays to the lord. In exchange, peasants could use small portions of land to produce their own food. Peasants were subject to the rules and taxes of the lord whose land they occupied.

A peasant couldn’t just take off and go looking around the mountains for gold. He would have to cross into different lands that are owned by different lords. Not to mention he was obligated to work for his lord and nobody else. It would be hard to prospect for minerals if you are tied to a very small plot of land.

Across much of central Europe, free miners were allowed to roam freely across land boundaries of land-holding lords and claim and work the deposits that they found. Since miners possessed the necessary skills and knowledge to exploit subsurface mineral deposits they were always welcomed by local authorities.

The free miner who made a discovery would be awarded a double-sized discovery claim along the vein. Later miners would only be allotted a single claim. In medieval Europe, a claim was called a “meer”. The head meer belonged to the miner who discovered the vein and all other meers were measured off of the head one. This practice continued well into the gold rushes of North America. A medieval free miner would typically not be required to pay for the registration of a claim, the royalty was enough.

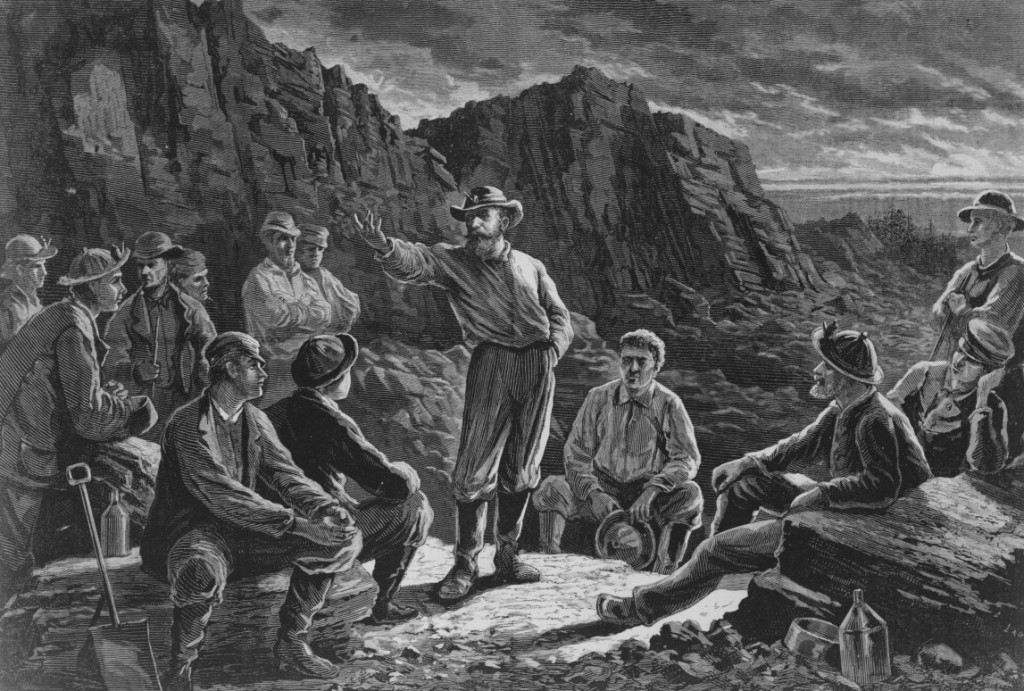

Free miners in Germany and Austria developed a system of democracy that was independent of the king, government or lords of their time. In each mining district, the miners got together and elected a “Bergmeister”. The Bergmeister acted much like the gold commissioner in more modern times. He would determine the size of a claim that is to be awarded upon discovery, settle disputes about claims and so on. If the miners weren’t happy with the Bergmeister they would replace him with a more competent one. There is a ton of information of the systems and techniques of mining in the middle ages in an old book called “De Re Metallica”, published in 1556. The title is Latin for “On the Nature of Metals”.

The rules, laws, and practices of free mining communities were brought to England before the invasion by the Normans in 1066. There were several distinct free mining districts in medieval England. Districts were built around a specific commodity such as tin, coal, lead, zinc, and gold. A miner could explore anywhere in his claim regardless of land ownership. A claim was permanent, transferable and heritable as long as he kept up the required work obligations and paid the required royalty.

One of the first written laws regarding free miner’s rights was passed by the Bishop of Trent (modern-day Italy) in 1185. Under that law, the state held all mineral rights. Miners were permitted to freely enter the land to explore and mine provided that they shared the wealth with the state.

Miner’s Law

Free miners typically had immunity from the jurisdiction of the surface owner’s courts and had immunity to common-law. Different lords had different laws, different taxes and so on. Since free miners could roam freely, crossing different land boundaries they needed their own set of laws to provide some sense of continuity. Free mining districts had free miners’ courts which were controlled by the mining community. The concept of miner’s law lasted for centuries and even played a role in the gold rushes of Western North America from California to the Yukon.

Across medieval Europe, there were two main types of free miners. In more populated areas such as Southern England, the free miner system was community-based. Free mining communities existed where miners belonged to a self-governing community outside of the feudal hierarchy. In these areas, miners would work a claim in close proximity to other miners for decades and sometimes even passing on their claim to their descendants.

In the mountainous areas such as Northern England, Scotland, Germany, and Austria claims were spread out and miners would act more individually. In these areas, it was important for a free miner to be able to explore vast areas without being bound by individual landowners.

Both systems influenced the development of mining rights during the gold rush periods and many of the concepts still exist today. A free miner today in BC still has the right to roam freely in search of untapped mineral deposits, although there are a few limitations.

A free miner’s claim was not a standard amount of surface areas such as an acre, hectare or anything like that. The area that a miner was given depended on the strike and dip of their vein. A standard claim was 100 feet along the vein and a width of half the length. The strike of the claim was measured from the apex (outcrop) and could slope downward or lie flat with the land.

A steeper dipping vein would provide a smaller surface area for the claim. Free miners measured claims this way since a steeper dipping vein provided more ore per the same amount of area.

Since the amount of ore was the whole point, this system was considered fairer among free mining communities. This concept followed European settlers into the New World. During the homestead period of Western Canada and the United States settlers were given a predetermined amount of land while miners were given more freedom depending on the geology.

Property during medieval Europe was controlled by feudal lords. Many landowners had large swaths of land under their control and needed information about the geology and mineral deposits on their lands. Free miners were able to develop knowledge of geology due to their right to wander without concern for legal boundaries with large districts.

Medieval Lords commonly permitted free miners to operate on their lands in exchange for mining and geological information. Much as we do today with work and assessment reports as part of the upkeep of modern claims.

The California Gold Rush

At the onset of the California Gold Rush in 1848, the territory of California was only recently transferred to the United States from Mexico. Congress had not yet set up any kind of local government and there were no laws in place to govern the practice of mining. The 49ers were literally left to their own devices.

Each camp developed its own set of rules. Across all districts, miners asserted a universal right to free prospecting and mining on previously unclaimed lands. They developed systems for dealing with staking, noticing, acquiring and abandonment of claims. They dealt swiftly with proven claim jumpers. There were no royalties paid to any government but fees were collected to fund the local miner’s collective. They imposed a rule of one claim per man and work requirements. They also had a rule that allowed no more than one-week absence or your claim would be forfeited.

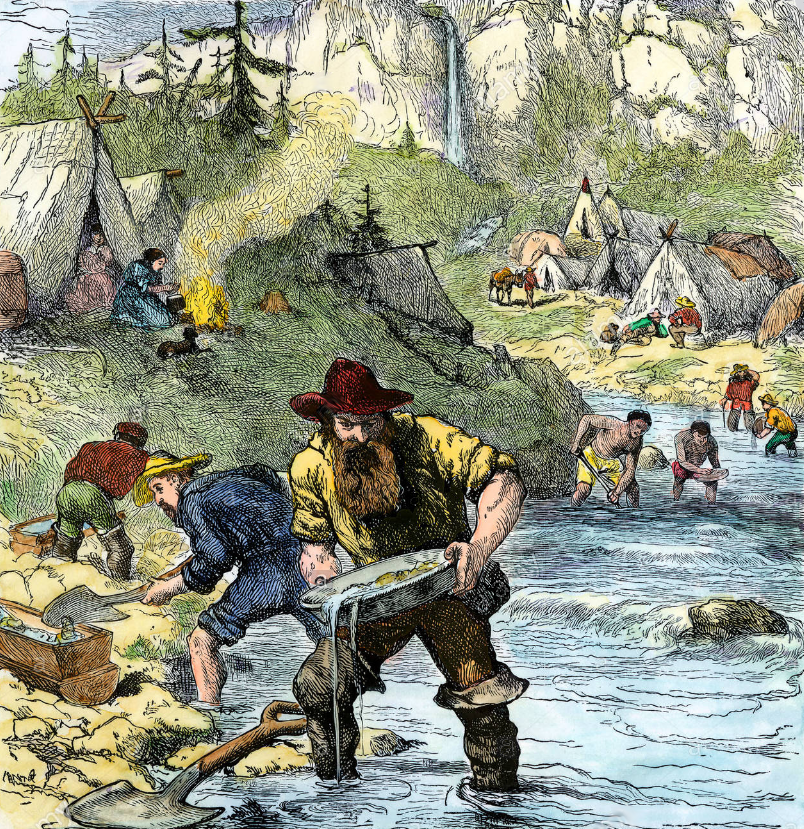

As discoveries slowed down in the California gold fields prospectors moved to other areas such as Australia, Colorado, Oregon, the Fraser River, Cariboo, and the Yukon. The principles developed in the California camp laws carried with them but had to be adjusted since the new districts actually had governments and laws while California didn’t enact actual public laws until two years after the first gold miners arrived.

The Australian Gold Rush

When the gold rush broke out in Australia in 1851 miners were shocked to find that New South Wales already had a government, property law, courts, military and police. That was a big difference from the wild west of the lawless California gold fields. There were some major conflicts as Australia tried to impose land restrictions, fees and various other rules on the miners.

In the end, a compromise was made and Australia’s Gold Fields Act was passed in 1854. That piece of legislation was based on the European principles of free mining and the lessons learned in the California gold fields. The act protected the miner’s right to free entry, the right to discovery, a personal right to the minerals in place, the right to occupy the claim and a right to participate in the making of local mining rules.

The Fraser River Gold Rush

With the influx of 30,000 prospectors, mostly American, the British population of 100-200 people was completely overwhelmed. Britain’s claim to present-day BC was under threat.

With the madness of the California gold rush fresh in people’s minds, the young government had to act quickly. HBC Governor James Douglas stationed a gunboat on the Fraser River to intercept gold rush miners to collect mining licenses and lay down the law. Great Britain acted quickly to make BC a crown colony on August 2, 1858.

It was the gold rush, not fur trading that really made BC part of the British Empire and subsequently part of Canada. Our mining laws were imported from Great Britain. Much of our current mining law in BC came from the passage of the Gold Fields Act in 1859.

The Gold Fields Act was strongly based on the legislation passed in Australia three years prior with the same name. The three principles of the free miner were paramount: the right to discovery, the right of entry to explore and the right to miner’s law. Under the new act, any person 16 years of age or over could obtain a Free Miner Certificate for the cost of one pound. An FMC gave its holder (the “free miner”) the right to freely enter onto, and stake a claim, on any un-staked area of Crown land – including private property and First Nations’ territories.

Governor Douglas’ law differed from the Australian law in that it allowed more freedom for miner’s boards. The rules for claim size and the ins and outs of staking a claim varied between mining districts. The government was small and the territory was vast.

The BC government didn’t have the means or the manpower to police all details of mining. They set the ground rules, issued a free miner’s license and let the miners boards police themselves. The large geographical areas and differences among deposits necessitated that claim size, rules and laws be different across the province. The local miner’s boards were able to rule by consensus.

Vigilante justice and decisions by majority vote prevailed in the camps. In time the North West Mounted Police (the predecessor to the RCMP) took on a larger role and established itself in most of the gold rush towns. By the time of the Klondike Gold Rush, there was a substantial NWMP presence in the gold mining areas.

Changes in Legislation

In 1891, provincial legislation formally recognized locations in which free miners could not enter onto and prospect for mineral claims. This included towns, private homes and Indian reserve lands. Today, areas that do not carry the automatic right of entry include land occupied by a building, the 75m of land directly surrounding a private residence (if that area is lawns, gardens etc.) and crop lands.

During the gold rush era (1850s to 1910s) most of the areas being prospected and mined took place on unoccupied frontier land. There were very few people around. On top of that, the techniques of placer mining consisted of pans and rocker boxes. In later years when miners employed more capital-intensive techniques like damming and hydraulicking, water licenses and land use started to become an issue.

In 1911 the Mineral Easements Act was passed. This new act established rules for right of way access to mineral and placer claims over private land. These rights of way included the right to construct the infrastructure required for mining and the right to use existing roads in aid of their mining activities

Under this act, only thirty days’ notice (including an advertisement published in the British Columbia Gazette and in a local newspaper for one month) was required for the establishment of a right of way that could last over an area of land for generations and permit the construction of a pipeline, tramway, and movement of heavy machinery.

Today, the ability for free miners to secure a right of way over private land, without the consent of the landowner, is preserved under section 2 of the Mining Right of Way Act – a legislative successor of the Mineral Easements Act of 1911.

Modern Laws on Free Miners in BC

Much of the free miner system remained the same until the 1990s. In 1995 the Mineral Tenure Amendment Act was passed, which added some limitations to mineral rights and activities on private lands. The act prohibited free miners from “interfering with any operation, activity or work on private land”. That was the first major restriction on the free entry system since 1891.

In 2002 amendments to the Mineral Tenure Act, removed the prohibition against free miners and recorded holders from interfering with any operation, activity or work on private land. The amendment provided that interfering with privately held land was permissible, so long as it was minimal and the private owner was compensated.

On January 12, 2005, the whole game changed. BC initiated the online staking system that we know today. Prospectors were no longer required to physically drive claim stakes into the ground, staking could now be done with the click of a mouse. This opened the door to a whole new level of speculation. The number of staked claims grew exponentially. Free miner rights remained intact.

In 2008 the Mineral Tenure Act and Mineral Tenure Act Regulation were amended once again to require that any person beginning mining activities on private land had to give notice at least eight days prior to beginning any mining activity. That law stands to this day. A free miner still has the right to occupy private property but must give a minimum of 8 days’ notice prior to occupation. It is important to note that notice does not require consent. A free miner must notify private landowners but does not need their permission to occupy private land for the purposes of mining.

The current law is specified in the Mineral Tenure Act of British Columbia.

The restrictions on land are broken into two categories. Free miners who hold a title and those who don’t.

As specified in section 11 of the act, the current restrictions on private land where a free miner doesn’t hold a claim include:

- land occupied by a building

- the curtilage of a dwelling house,

- orchard land

- land under cultivation

- land lawfully occupied for mining purposes

- protected heritage property, except as authorized by the local government

land in a park

Free miners without mineral tenure have rights to explore and search for minerals on most land. In BC a free miner can access any private property as long as proper notice is served and none of the above restrictions apply. That means that as long as you serve notice, you can explore freely on pretty much any private property in BC. The main exceptions are farms and land with a house on it.

If a free miner holds a claim overlapping private property there are less restrictions on access:

- There is a mining prohibition in that area under the Environment and Land Use Act

- The area is a designated park under the Local Government Act

- The area is a designated park or ecological reserve under the Protected Areas of British Columbia Act

- The area is an ecological reserve under the Ecological Reserve Act

- The area is a protected heritage property.

When a free miner holds an active tenure the rules change slightly. Access to private land is much less restrictive. Not only does a free miner have access to the land, an active tenure give the right to use the land for all operations related to the exploration and development or production of minerals or placer minerals.

Section 14 of the Mineral Tenure Act which states:

Subject to this Act, a recorded holder may use, enter and occupy the surface of a claim or lease for the exploration and development or production of minerals or placer minerals, including the treatment of ore and concentrates, and all operations related to the exploration and development or production of minerals or placer minerals and the business of mining.

The concept of the “Free Miner” has deep historical roots and much of the free entry system and principles of the free miner are still present in BC laws and practices. The three core tenents of the free miner The right to discovery, Freedom to roam and self-government are built into our current laws. The miner’s meetings and self-government are no longer necessary as we now have strong governments with actual mining laws in place.

The free entry system is often misunderstood by people who aren’t familiar with the intent and history of the system. Private landowners are often surprised to learn that they have to allow miners onto their property. As a result, the free entry system is under threat by people outside of the mining community. Ontario, Quebec and the Northwest Territories have abandoned free miner’s rights due to public pressure.

The same principles that created free entry in Roman and medieval Europe are true today. In order to explore for minerals, it is necessary to have access to the land. If we lose the free entry rights then it will become harder and harder to discover and produce the minerals that our society needs.

When you hold a Free Miner’s Certificate you belong to a long history of free miners. It’s not just a piece of paper. The FMC represents freedom in the true sense of the word. A free miner means belonging to a community that built its own rules and paved the way for modern society. We might have modern tools, advanced technology, and modern government but a discovery today is no different than a discovery in medieval Bavaria. All miners strive for independence and to feed their sense of adventure.

Overall good background

Some typos.

Some bullet edits.

It was NWMP not RCMP in Yukon gold rush.

Thanks for the feedback. I didn’t know I was going to be graded.

You are correct that it was the NWMP during the gold rush. I’ll update the post to represent that.

Hi,

I am 63 and living in Canada since 2010. Just a few weeks ago I got my FMS. I am equipped with all the stuff I need – metal detector and gyrocopter included. But the first try to go to the site I want to test for gold showed me that a “free minor license” is not free and I have to live for the “father state” all sites where I could just guess existing corn of gold. And I can not use my equipment at all – except for my plastic pan and shovel.

That is ridiculous.

I was dreaming of Canada as it would be a free (!) country…

Hi Peter, there are rules for everything. The free miner rights mostly require that you have a claim. Once you have a claim you can use any equipment that you want. For machine assisted work you need to file some paperwork.

Did you say you have a gyrocopter? That’s an interesting piece of prospecting equipment.

WCP actually has a mining club with lots of claims. You can use you equipment on our claims if you join the club. Send us a message from the contact form:

https://www.westcoastplacer.com/contact/

Graded A+ Great article, very well written!

Can you use a desert fox for prospecting? It is a self contained unit that uses a recirculating amount of water, a spiral wheel and a battery. It has a titled spiral wheel that sorts it out. Would that be considered a machine in legislation sense? Thanks.

That’s not really related to the subject of Free Miners but in BC, as long as you’re on an active placer claim with permission that would be allowed. The fact that’s it’s a machine doesn’t make much difference regarding permits. You need permits when it comes to things like machine-assisted ground disturbance and large volumes of water intake. It would not be legal to use a Desert Fox if you’re not on an active placer claim.

A small gold wheel wouldn’t really help you in prospecting though. Those are more for cleaning concentrates than running raw material. There are more appropriate devices for prospecting.

Where do I apply for a FMC ?

First you need to register for a BCeID, then you can get your FMC. The Free Miner’s Certificates are managed by the Mineral Titles Branch.

Here’s the government’s document on how to apply: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/mineral-exploration-mining/documents/mineral-titles/mt-faqs/faq_fmc.pdf

Registered BCeID, FMC Free Miner’s Certificates holder.

Looking forward to some adventures new to me! Found website while google searching.

Panning kit and Desert Fox patiently waiting…