Mining under Earth’s oceans is just starting to happen. We have gotten pretty good at mining deposits that are accessible by land but 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water. To date no large scale mining operation has succeed under the ocean which means that it’s all virgin ground.

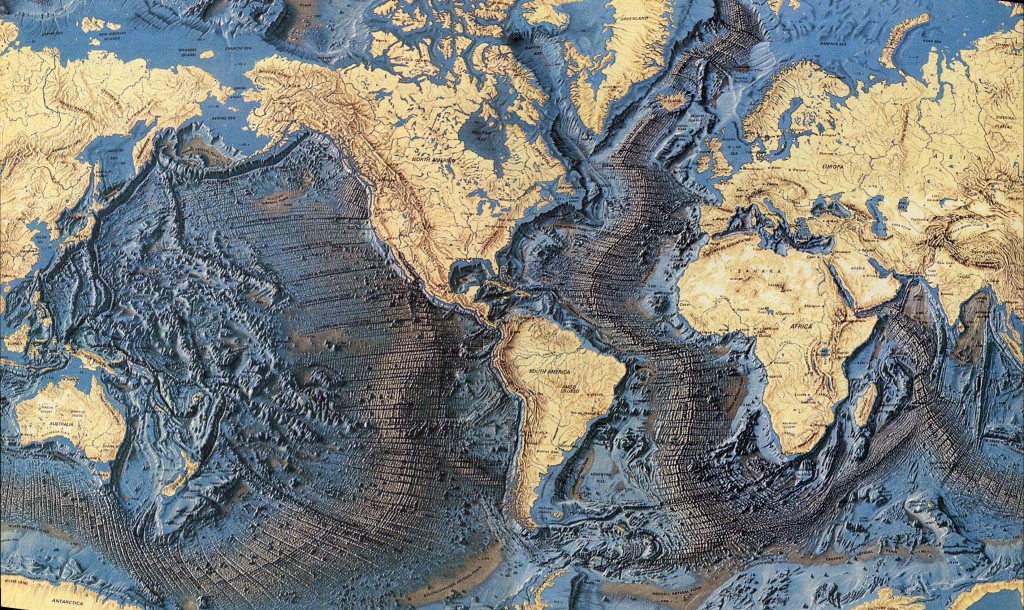

Amazingly the human race has spent more time and money exploring outer space than we have under our own oceans. Over 500 people have been to space while only three have ventured to the deepest part of the ocean, the Mariana Trench. We have better maps of the surface of Mars than the bottom of the ocean, although the ocean maps are pretty cool.

The same geological processes that happen on land also take place under the ocean. There are volcanoes, mountain chains, faults and earthquakes. All the same types of mineral deposits occur under the ocean such as epithermal gold, porphyry, and placer. There are also diamond pipes, massive sulphides and everything else that we mine at the surface.

Deposits

The ocean also has types of deposits that we can’t find on land. One special mineral deposit is called Polymetallic Nodules. These are concretions of metallic minerals that occur under the ocean. The nodules grow sort of like stalactites do in a cave, over time layers of metallic minerals precipitate out of seawater and add to the nodule. The growth of nodules is one of the slowest known geological processes taking place at a rate of one centimetre over several million years.

Polymetallic nodules are roughly the size and shape of a potato and contain primarily manganese as well as nickel, copper, cobalt and iron. They can be found on the sea floor or buried in the sediment. Nodules can technically occur anywhere in the ocean but seem to be in greatest abundance on the abyssal planes around 5000m deep. Nodule mining would be similar to placer gold mining except under water.

Anouther resource that is unique to the ocean floor is Ferromanganese Crusts. These are similar to nodules but occur as a coating on other rocks. These crusts can be found all over the ocean with thicknesses ranging from 1mm to 26cm. Ferromanganese crusts typically occur in the vicinity of underwater volcanoes called seamounts or near hydrothermal vents. Crusts with mineral grades that are of economic interest are commonly found at depths between 800m and 2500m.

Ferromanganese crusts are composed primarily of iron and manganese, hence the name. Typical concentrations are about 18% iron and 21% manganese. Cobalt, Nickel and Copper occur in significant quantities as well. Rare earth metals such as Tellurium and Yttrium can be found in metallic crusts at much higher concentrations than can be found on the surface. Tellurium is used in solar panels and is quite valuable.

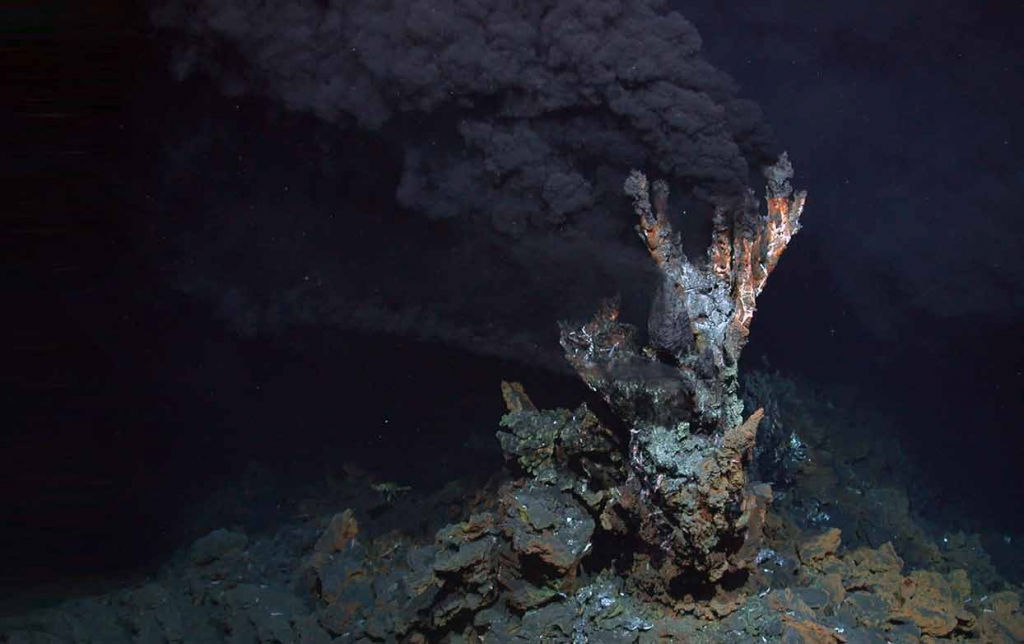

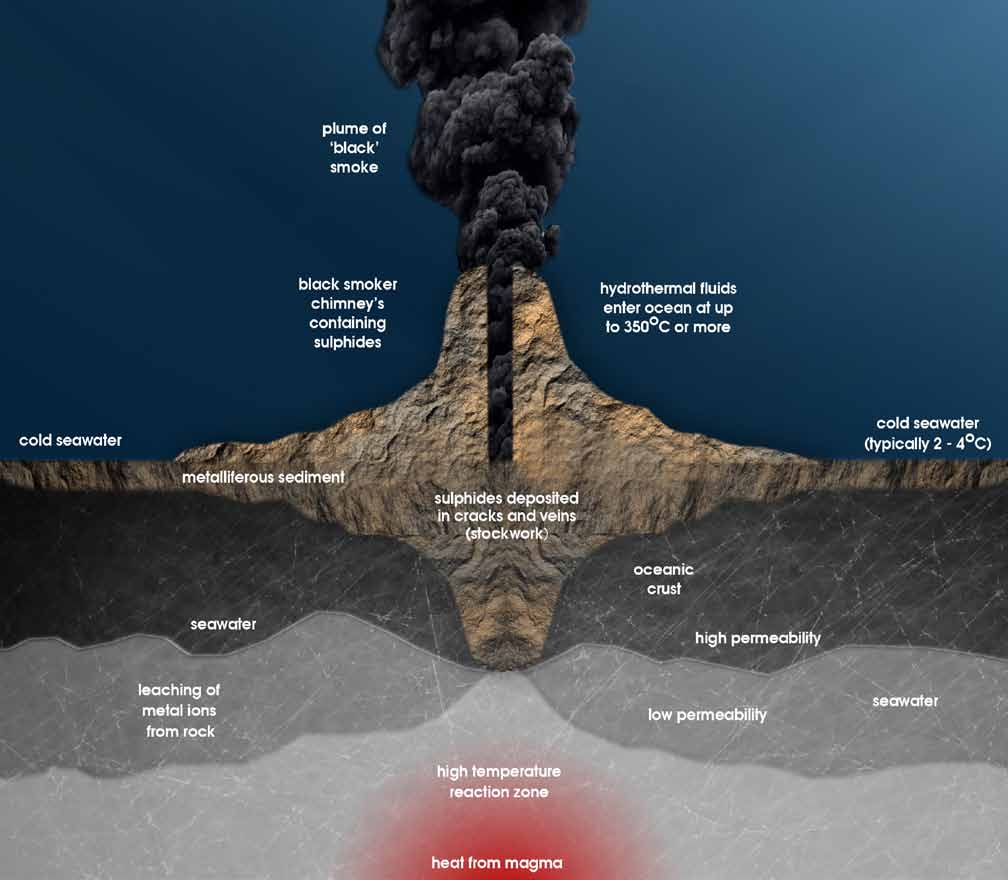

Sea-floor massive sulphides (SMS) are a younger version of volcanic massive sulphides (VMS). The two deposits are similar except that VMS are typically ancient and SMS are currently forming. SMS deposits occur where superheated hydrothermal fluids are expelled into the ocean. They typically form around black smokers near continental rift zones. SMS are know to hold economic concentrations of Gold, Copper, Silver, Lead, Nickel and Zinc.

Black smokers create SMS deposits by expelling superheated sea water that is rich in metallic elements. Cold sea water is forced through the sea floor by the pressure created from the weight of the water column above it. The water is then heated to temperatures in excess of 600°C when it is brought close to the magma that lies below. The heated water becomes acitic and carries with it a high concentration of metals pulled from the surrounding rocks. Once the hot, metal rich, water comes into contact with cold sea water the metals crystallize and deposit on and around the black smoker.

Mining

Large scale ocean floor mining has not taken off yet. Attempts have been made since the 1960s and 70s but failed due to technological and financial challenges. Small scale shallow ocean mining has been a lot more succesful in recent years. A great example is the popular TV show Bering Sea Gold. The miners in Nome Alaska are using modified suction dredges to comb the sea floor in shallow waters.

Currently proposed sea floor mining ideas are essentially super high-tech placer mining. They involve ways to dig through the surface layers of the ocean floor, bring the material to the surface and ship it to a processing facility. Its a lot like dredging but on a massive scale. As mentioned above, normal hard rock deposits also occur under the ocean but no plans have been proposed to build open pit mines under the ocean. That would involve all the challenges of building a mine on land with the added complexity of operating under the ocean.

Why is ocean floor mining possible now when it wasn’t 20 years ago? The answer comes down to one word, robots. The world of under water mining is the domain of autonomous drones and human controlled ROVs. Robot submarines are nothing new, they have been around since the 70s and have been used to explore depths of the ocean that are very difficult for humans to get to. UUVs or unmanned underwater vehicles are a little bit newer, they are basically an autonomous version of ROVs. Ocean mining robots have just been invented and share a lot of the technology used in these devices and they look like something straight out of science fiction.

The first deep sea mining project is currently being developed off the coast of Papua New Guinea. The project is called Solwara 1 and is being developed by a Vancouver BC mining company called Nautilus Minerals. Solwara 1 is a copper/gold SMS deposit with estimated copper grades of 7% and gold grades in excess of 20g/t and an average gold grade of 6g/t. The property sits at about 1600m depth.

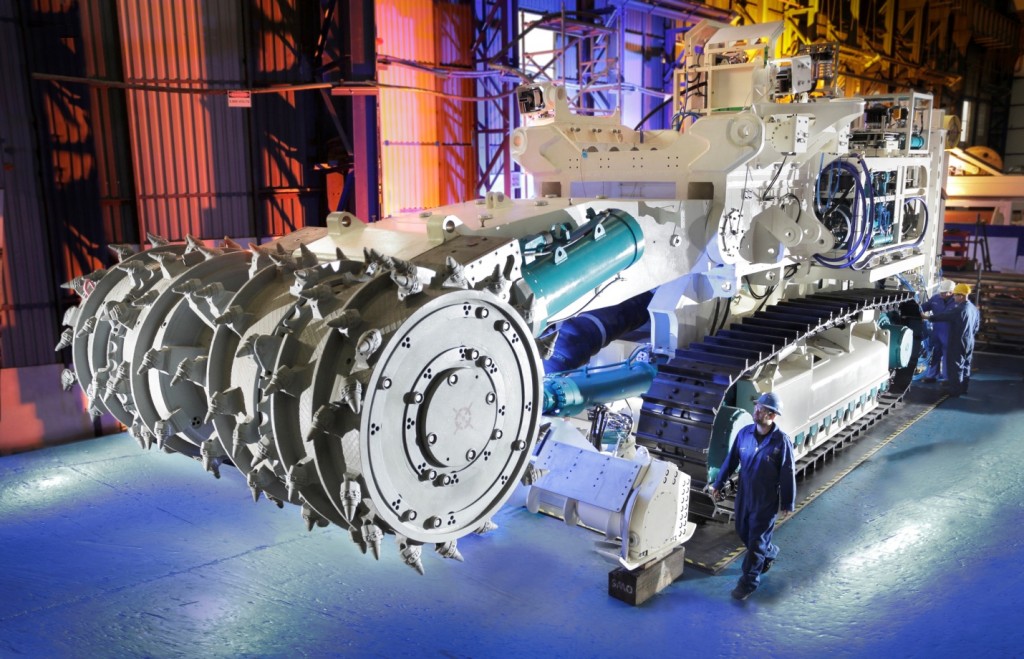

Nautilus has developed a suite of underwater mining robots and a complete system to mine the precious metal and bring it to shore. There will be the bulk cutter pictured above, an auxiliary and a collection machine. Please take a moment and marvel at these amazing achievements of engineering.

The Riser and Lifting System (RALS) is designed to lift the mineralised material to the Production Support Vessel (PSV) using a Subsea Slurry Lift Pump (SSLP) and a vertical riser system. The seawater/rock is delivered into the SSLP at the base of the riser, where it is pumped to the surface via a gravity tensioned riser suspended from the PSV.

Once aboard the Production Support Vessel the mined slurry will be dewatered and stored until anouther ship comes to take the material on shore for processing. The removed sea water is pumped back down the RALS which adds hydraulic power to the system. Pretty cool stuff! Check out the video below for an visual explanation of how it will all work.

Exploration

Ocean floor prospecting is not a good place to be gold panning or hiking around with a rock hammer. It is also difficult to take usable photos due to poor light and lots of debris in the water. So how do you explore for minerals in the ocean? Geophysics and robots.

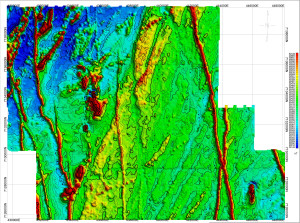

Geophysical exploration is not unique to the ocean. The same techniques are used routinely on land to find every type of mineral deposit. Ocean geophysics is also not new. The main workhorse of mining exploration is magnetometry. Which means mapping changes in earth’s magnetic field using a specialized sensor. The technique was actually developed to detect enemy submarines during World War II. Since then magnetometers and the science behind them have evolved into accurate tools to measure geology.

I’m using a proton precession magnetometer in the photo below. There is some sample magnetometer data on the left. Mag maps look similar to a thermal image except the colour scale represents magnetic field changes (measured in nanoTesla) instead of temperature.

Magnetometers are excellent tools for ocean mining exploration. They are not affected by the water and are excellent at detecting metallic anomalies. There are now underwater drones that can collect ocean magnetometer surveys without the need for human intervention.

Other geophysical techniques have been used in ocean mineral exploration. Electomagnetics (EM) techniques are also great tools for exploration under water. EM works in a similar way to magnetometry except that they emit their own source. Conventional metal detectors are actually a small version of an EM system. While mag passively measures Earth’s magnetic field EM measures the difference between a source and received pulse. EM also works great for discovering metallic anomalies and is being incorporated into autonomous drones as well.

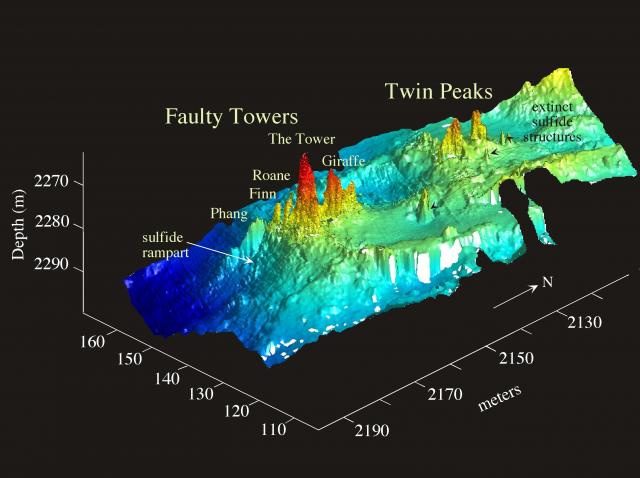

There are other types of ocean geophysics such as seismic refraction which uses a giant air gun to send a sound wave deep into the crust and measures the response on floating hydrophones. Sonar and other forms of bathymetry can provide detailed maps of the ocean floor. Bathymetry techniques can create imagery similar to LiDAR that is used on land.

Ocean mining is just in its infancy and some really cool technology is being used. Advancements in the robotics have allowed mining and exploration to be completed without a person having into enter the water. As technology advances further we will be able to explore vast areas of the ocean floor and discover immense mineral reserves that are presently unknown. It is estimated that we have only explored about 5% of the ocean floor, who knows what we’ll find down there?